| Introduction

After any election, narratives about “what happened” begin to develop that may or may not be data-driven and are colored by the elections’ outcomes. To provide a more focused, data-driven look into varied campaign communications, we collected and analyzed thousands of campaign communications across the 2018 election cycle.

Our analysis highlights the issues that received the most attention throughout congressional campaigns for the House of Representatives: political figures Donald Trump and Nancy Pelosi, issues like health care, Medicare and Social Security, taxes, and immigration. Despite Donald Trump’s ubiquity in the news media, our learnings showed that he received a relatively moderate amount of attention from congressional campaigns of either party. On the other hand, negative statements about Nancy Pelosi formed a central component of the Republican message. While Republican candidates focused on attacking their opponents, their Democratic counterparts were consistently issue-focused. In particular, Democrats emphasized a health care message: protecting people with pre-existing conditions, ensuring affordable drug coverage, and protecting the budget for Social Security and Medicare. Republicans, on the other hand, were more likely to rely on negative attacks and attempts to incite fear, from issues like Medicare and Social Security to immigration. The Republicans’ signature legislation of the 115th Congress, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, did not dominate Republicans’ message related to taxes. Rather, they reiterated a general anti-tax position while threatening that Democrats would increase taxes if in power. Democrats did not concede the issue of taxes and argued the Republican legislation primarily benefited large corporations and wealthy individuals at the expense of most ordinary Americans. Despite an economy many consider to be strong, it did not dominate the conversation as an issue. Republicans’ choice not to take credit for recent economic growth likely contributed to their loss of control of the House in this election. Finally, Republicans were staunchly anti-immigrant. Following Trump’s lead, Republicans increasingly referenced immigration as Election Day approached, race-baiting in an attempt to drive base turnout. Democrats focused overwhelmingly on health care during this time, as they had for the bulk of the campaign cycle.

Our analysis explored a range of other topics expected to be relevant in this election but found campaigns simply did not give these issues much emphasis. These included Brett Kavanaugh and the Supreme Court, foreign affairs, corruption, and the Mueller investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election. Other prominent national political figures, like Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton, and Paul Ryan, did not receive the volume of attention that either Trump or Pelosi received. For this reason, they are not discussed in this report.

This report explores each topic in greater detail. The data show that Democrats were more issue-focused and ran on constructive ideas related to kitchen-table issues like health care. On the other hand, Republicans were more reliant on attacks, fear, and negative messaging. This was particularly true on immigration, their emphasis on Nancy Pelosi, and their tax messaging. They appeared to be distracted from emphasizing the positive—an apparently strong economy. The Democrats’ constructive message around health care contrasted with Republicans’ negative tone, suggesting, at least for a party controlling both houses of Congress and the Presidency, that this negative vision was not a winning strategy. Furthermore, Republicans’ racist and xenophobic rhetoric on immigration did not help stem the tide of Democratic victories in this election.

| Methodology

To better understand the issues and messages driving congressional campaigns in the 2018 election, we collected and analyzed communications from candidates, party committees, and political action committees (PACs) in competitive districts according to the Cook Political Report as of October 8, 2018. This included 13 “likely Democratic” districts, 12 “lean Democratic” districts, 31 “toss-up” districts, 25 “lean Republican” districts, and 27 “likely Republican” districts. These communications were comprised of a variety of sources, including television ads, social media posts (from Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook) by candidates, party committee websites, campaign websites’ issues pages, and campaign Facebook ads. Television ads were transcribed and analyzed by their text content only, although we have retained an archive of the videos. Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram posts, as well as Facebook ads, were only analyzed by their text content; images were not included. Only English language content was analyzed.

We believe the data compiled is sufficient to provide a general overview of what issues Democratic and Republican campaigns prioritized in the 2018 cycle, how conversations shifted over time, and how both parties talked about issues in different parts of the country. We hope this analysis will provide a more complete and data-driven picture of the 2018 campaign season than post-hoc punditry usually allows. That said, while this content covers a broad range, including some of the most prominent communications from campaigns, it is not an exhaustive dataset.

A more detailed description of how this data was collected, limitations of the dataset, and a dictionary of keyword search terms is available in the Appendix.

| Overview

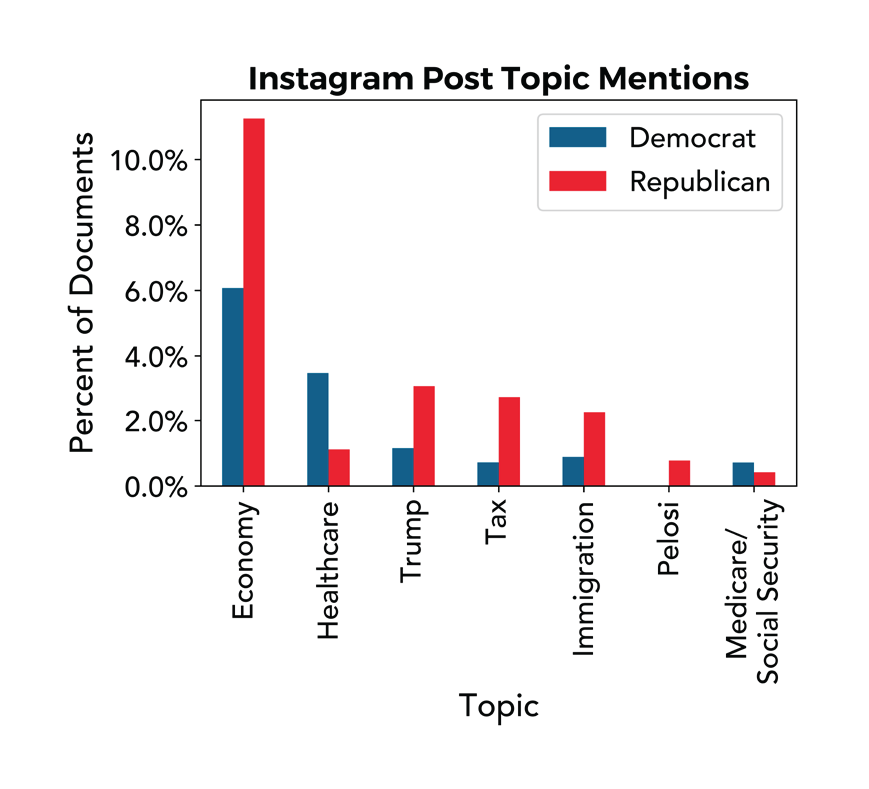

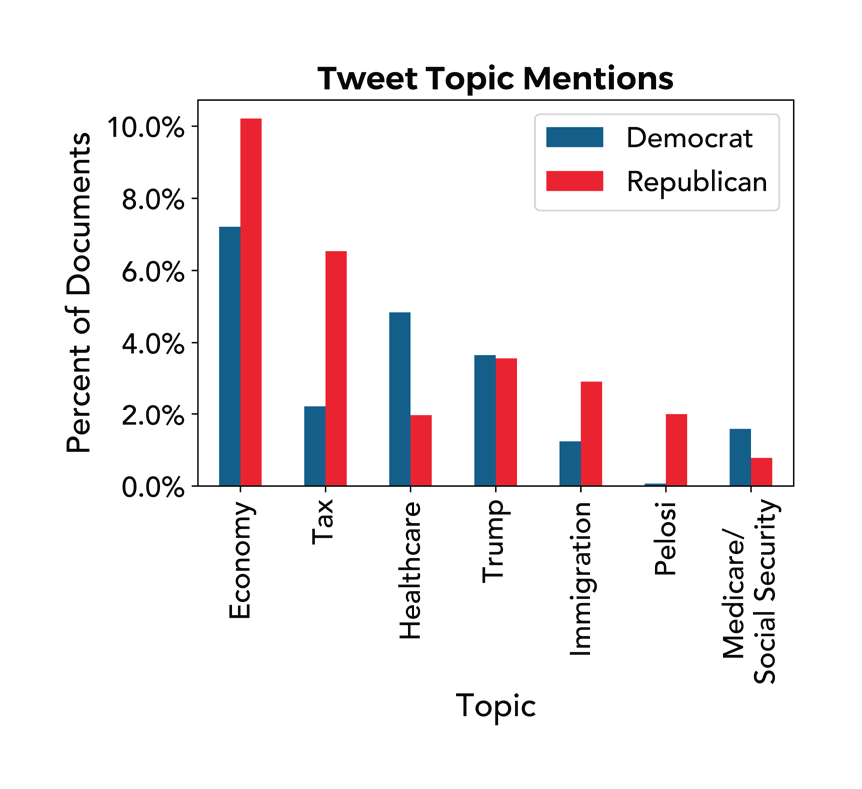

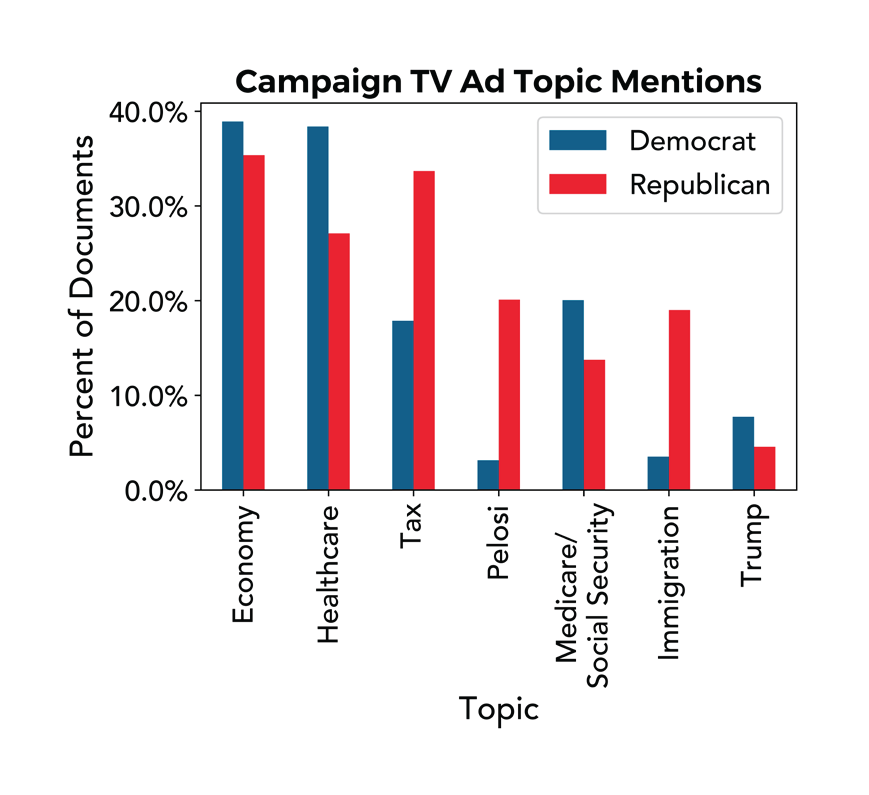

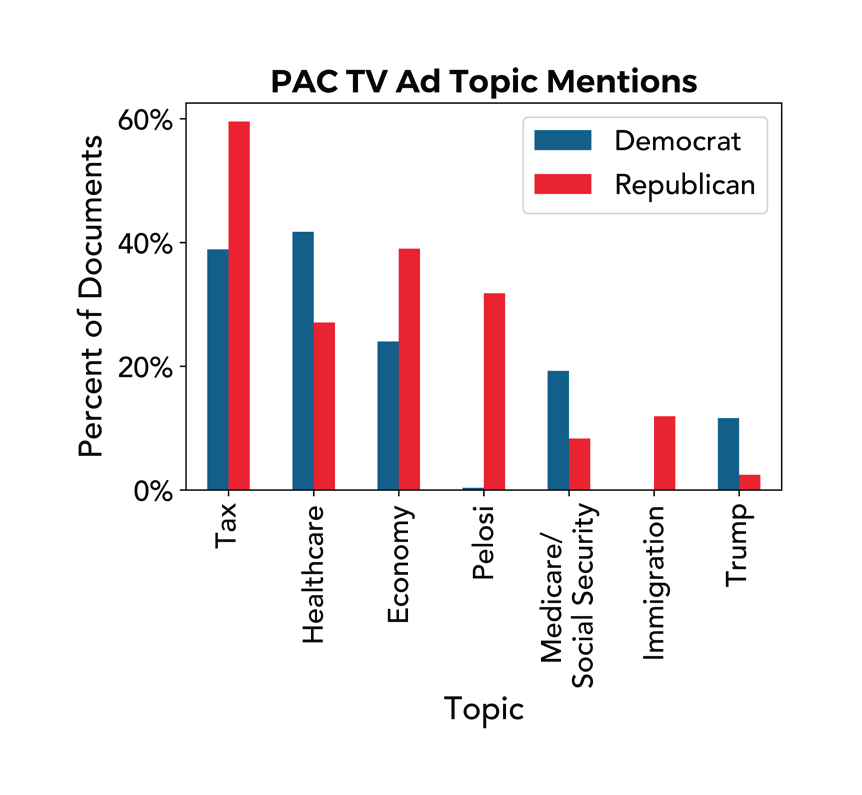

We surveyed the most popular campaign topics by medium to understand what messaging predominated for different audiences. Instagram posts were geared toward supporters and tended to be positive, while Facebook posts and Tweets were more interactive, personal, and casual. Television ads tended to embody the campaign platform, and PAC television ads reflected the interests of the PAC and may or may not have been in line with the campaign’s priorities.

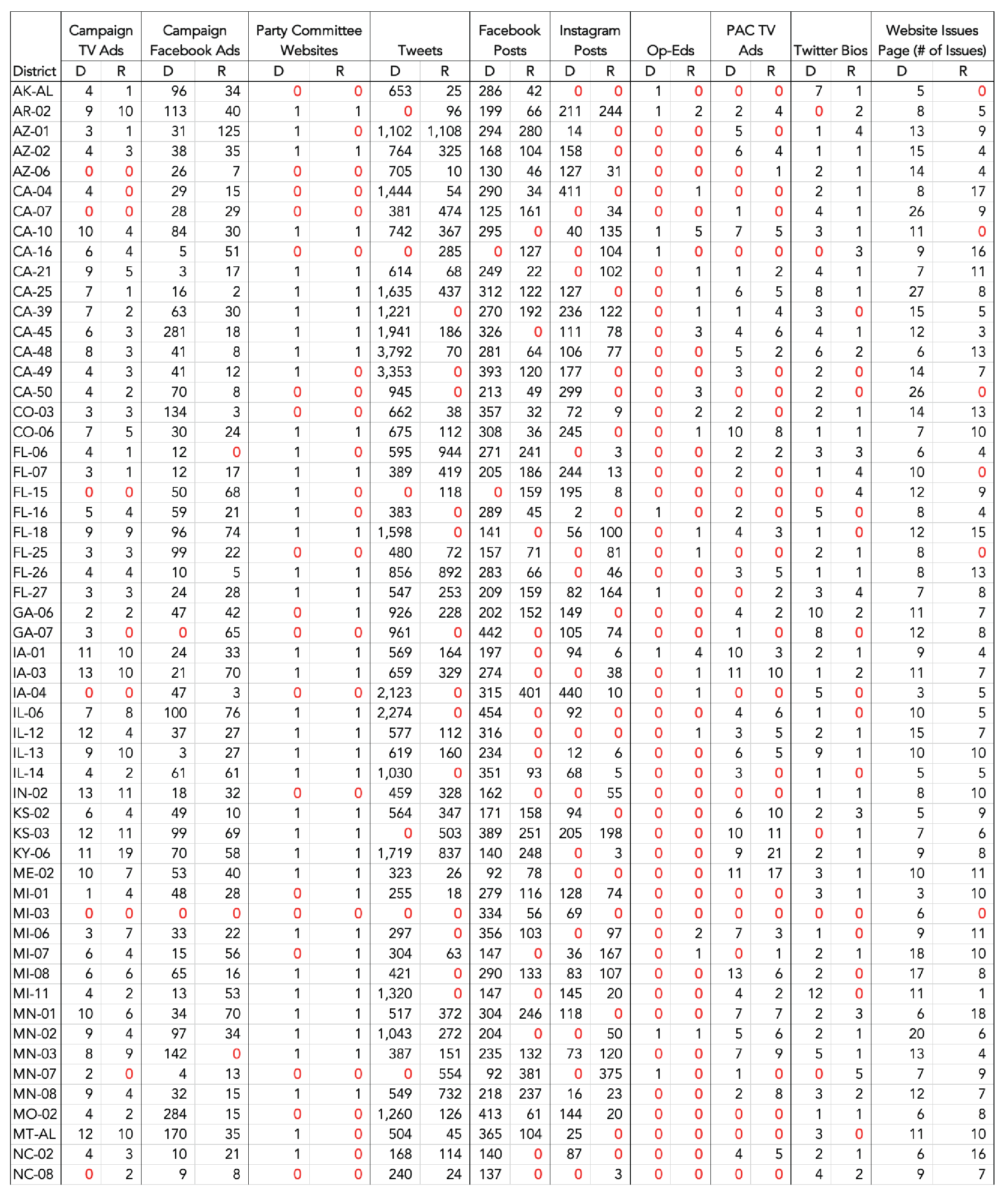

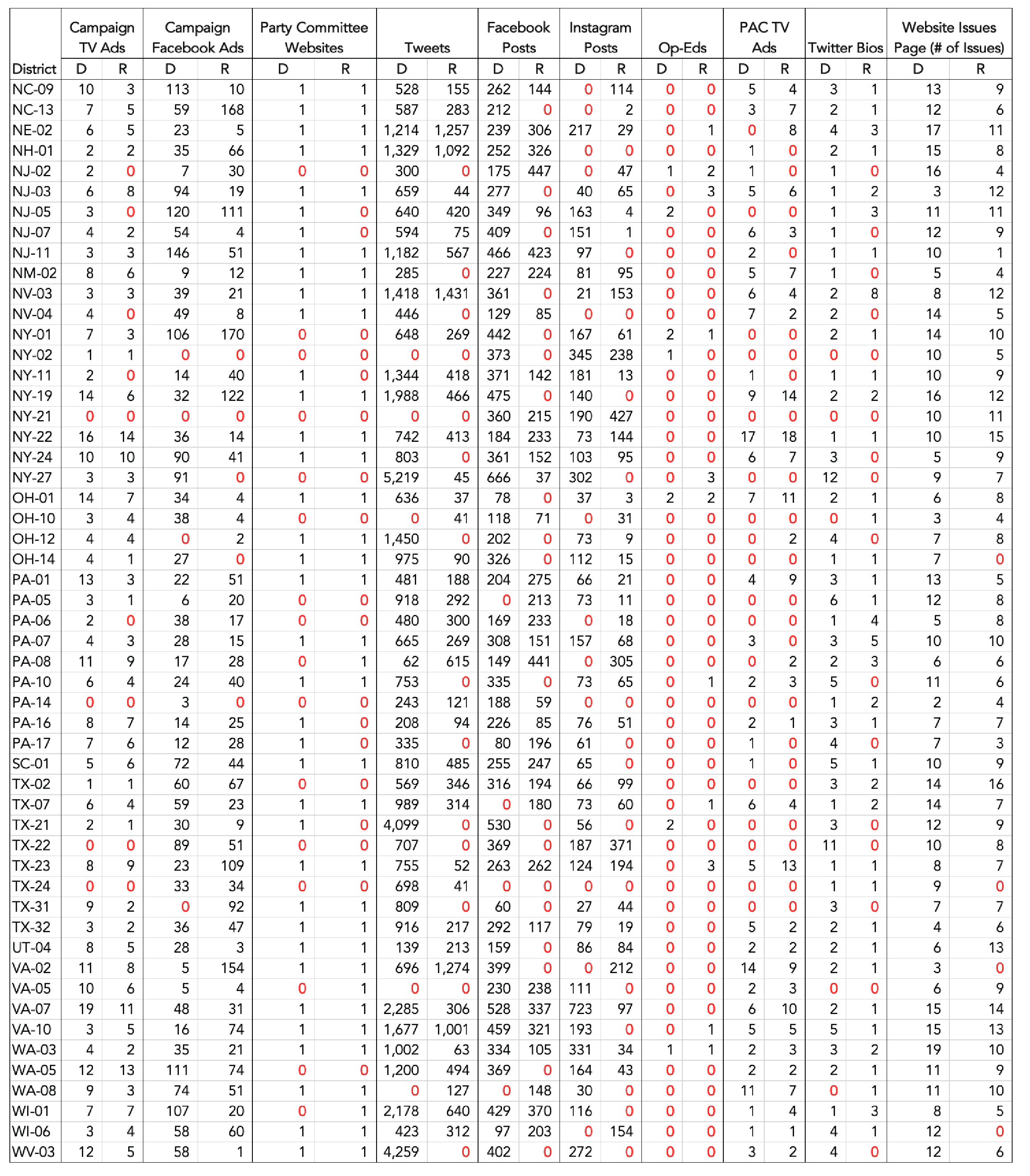

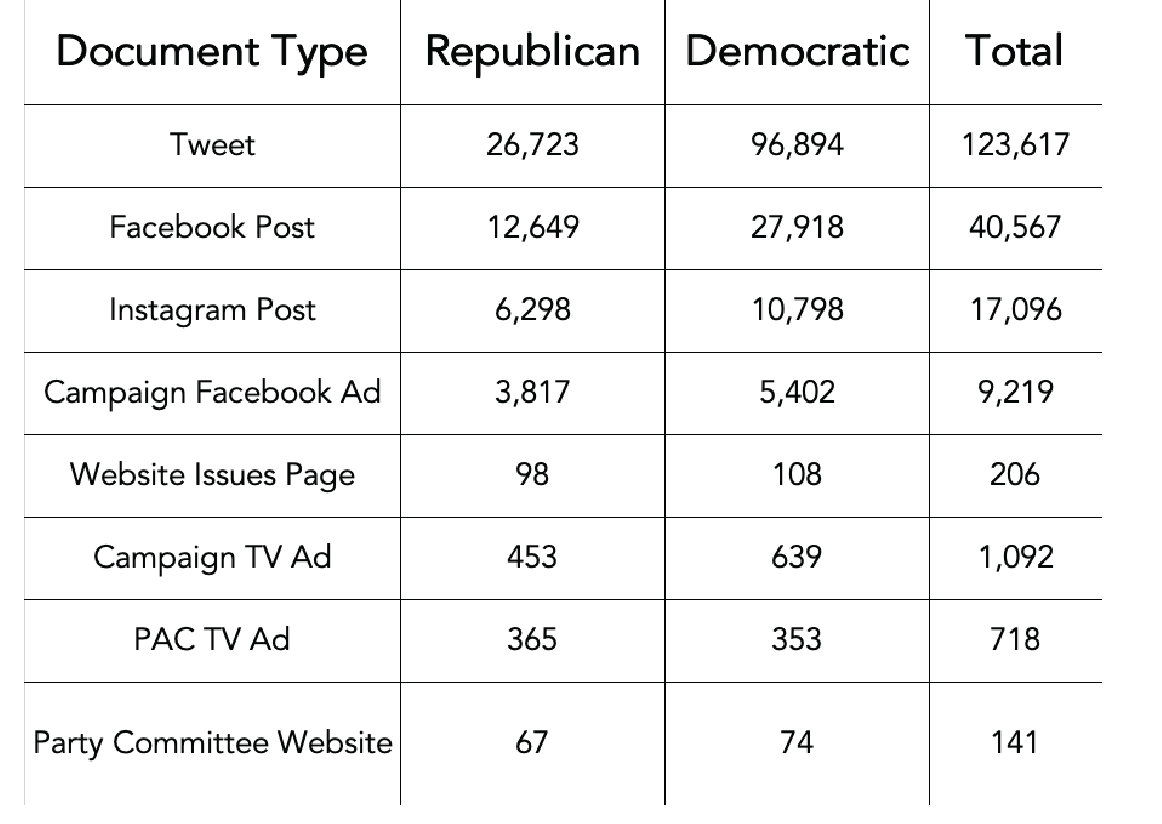

Stylistically, the two parties focused on different means of communicating with voters. The table to the right shows the average number of campaign communications in each district. Democrats were far more active on social media, had more issues listed on their websites, and ran more television ads. The only medium in which Republicans were more active than Democrats was in television ads run by PACs. Democrats ran active campaigns in nearly every competitive district, putting them in position to capitalize on trends that set up a bad year for Republicans: the party of an incumbent president tends to lose seats during midterms, and Trump is historically unpopular. Whether due to lack of funding, lack of staff, or lack of interest, Republicans lagged significantly in outreach.

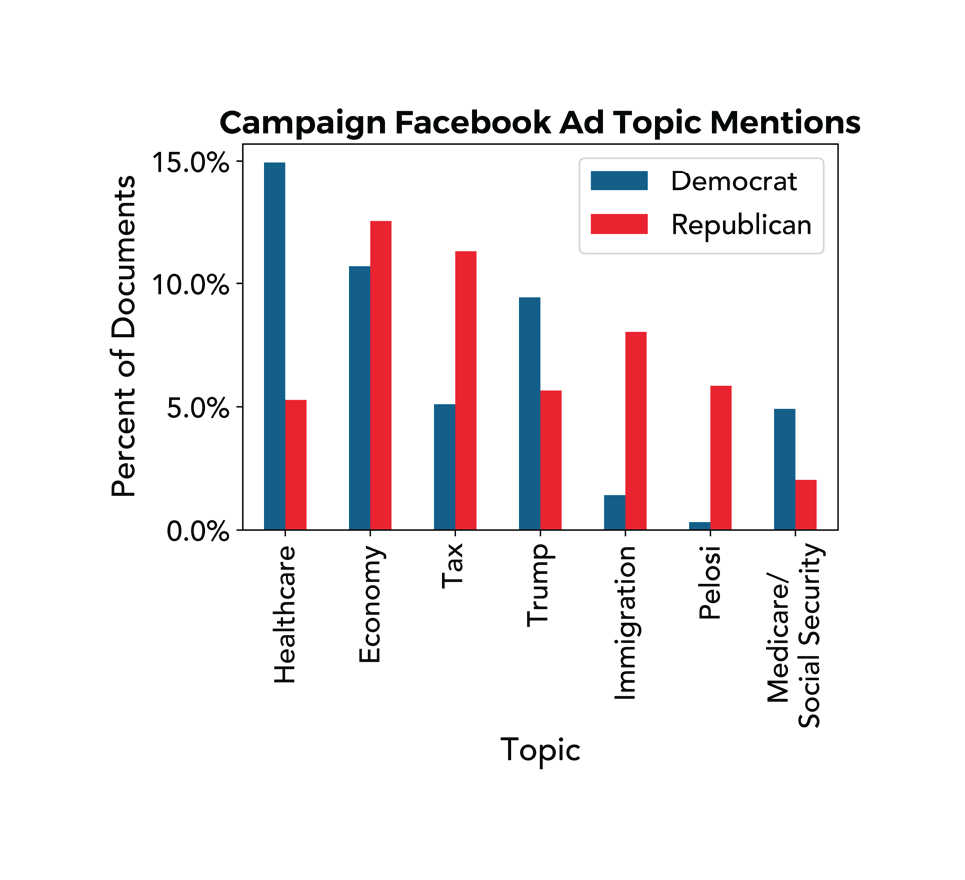

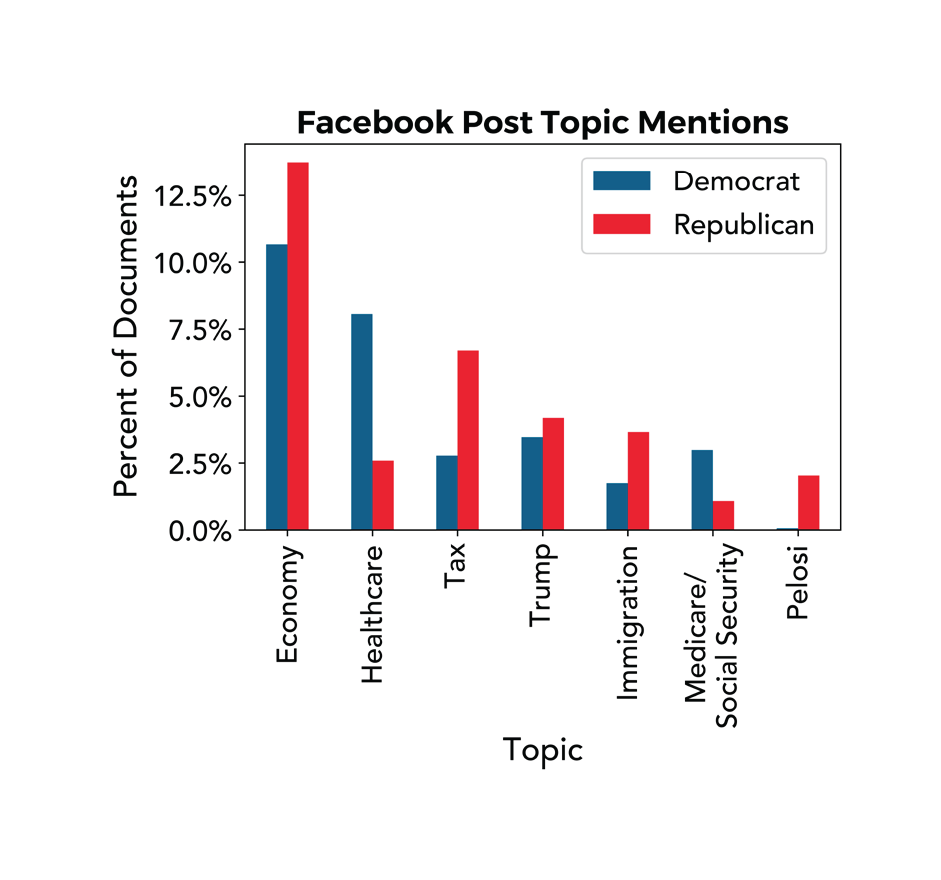

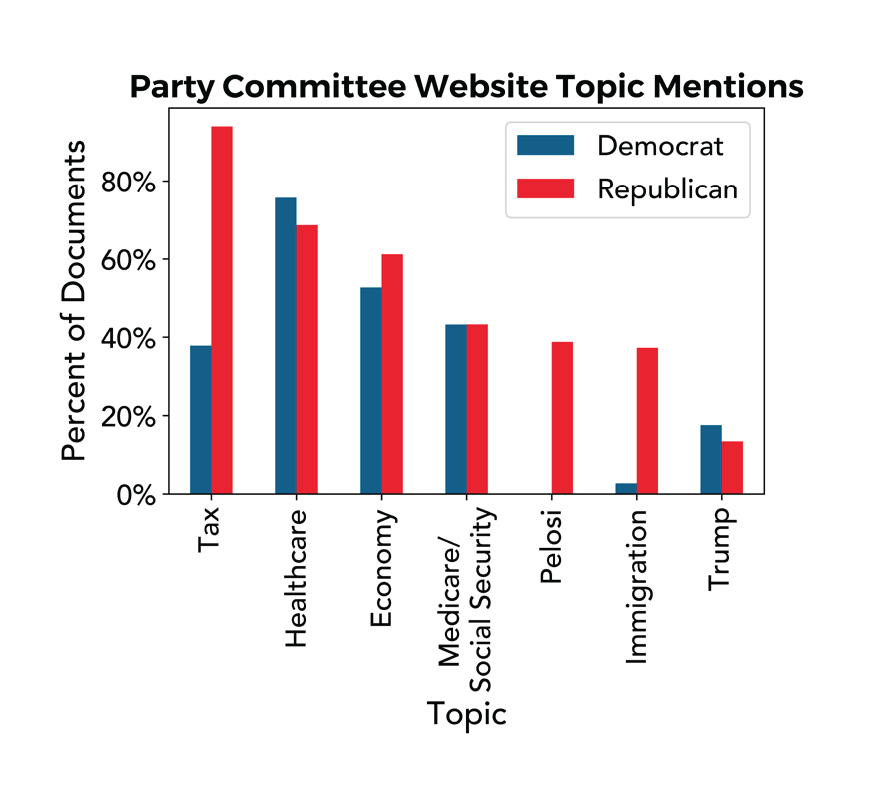

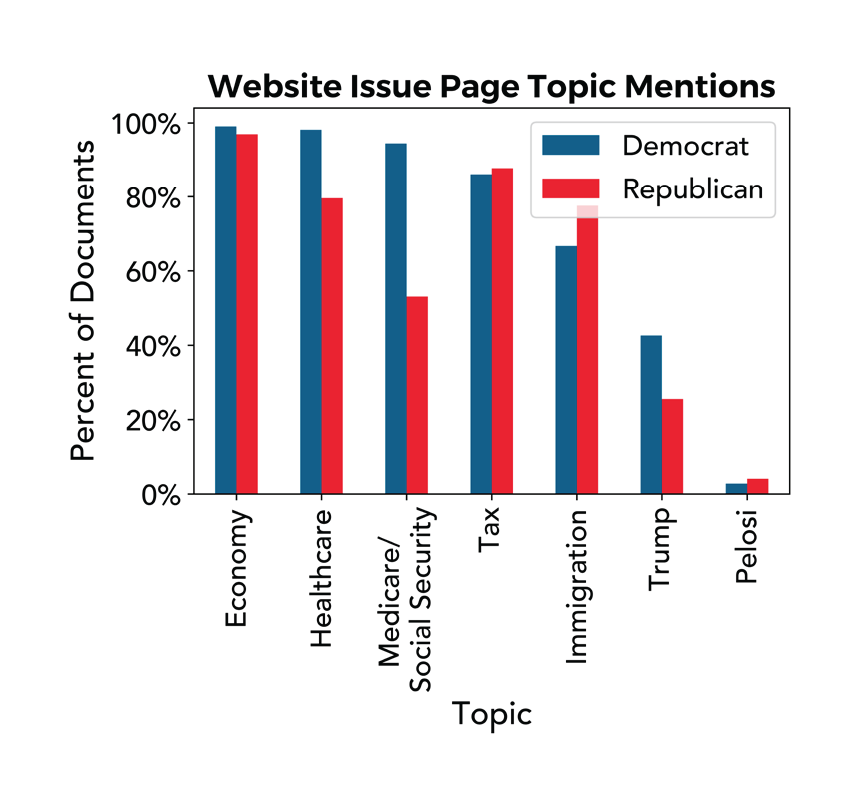

Across most platforms, the economy, health care, and taxes dominated.

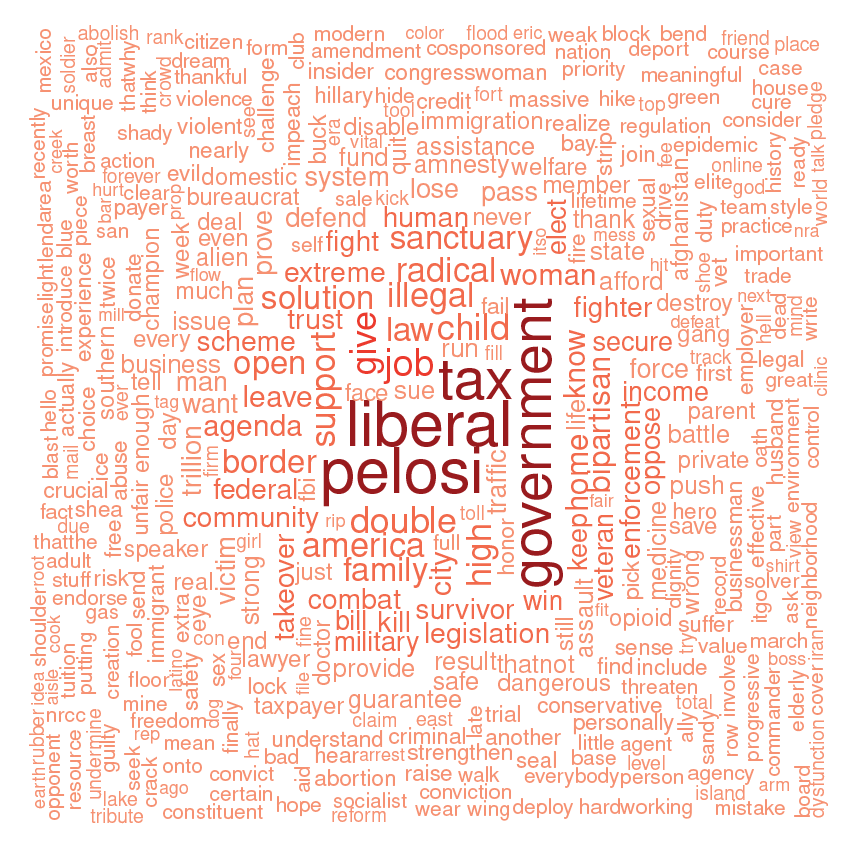

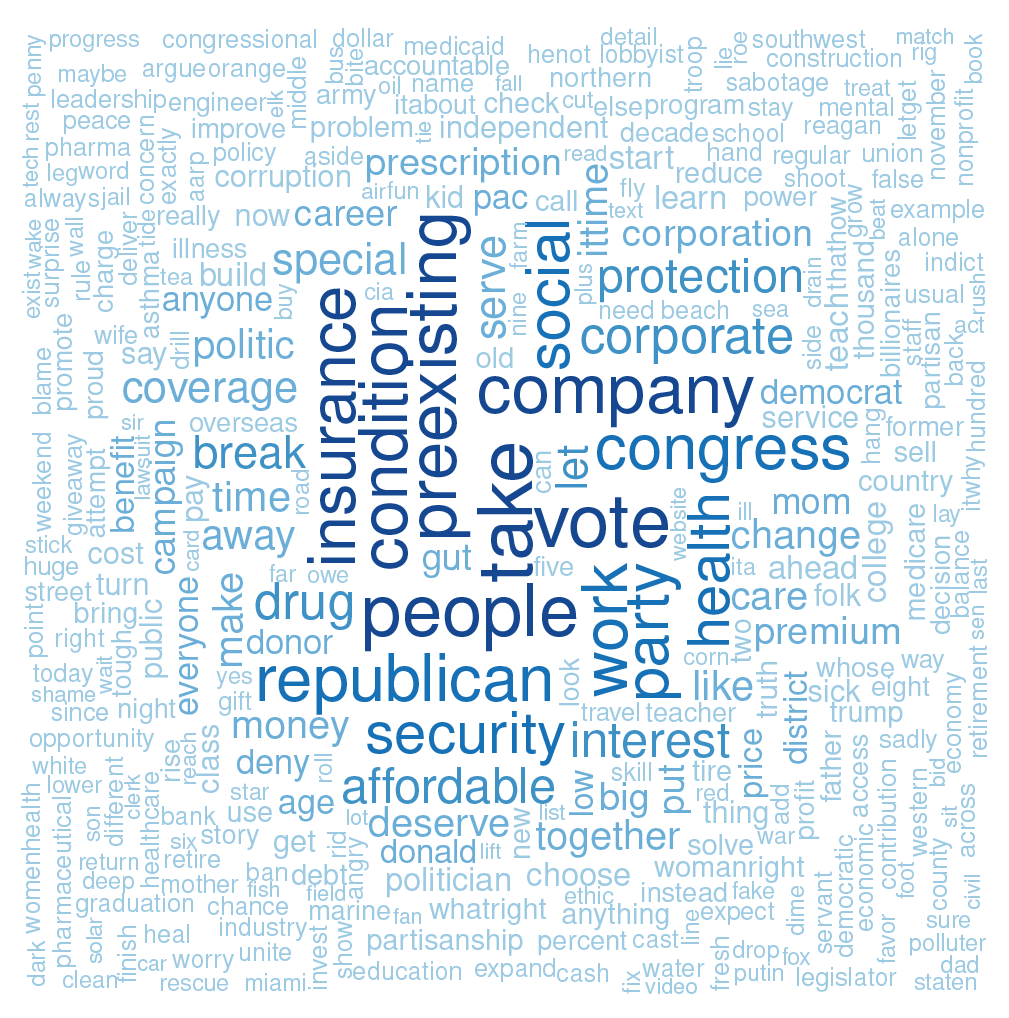

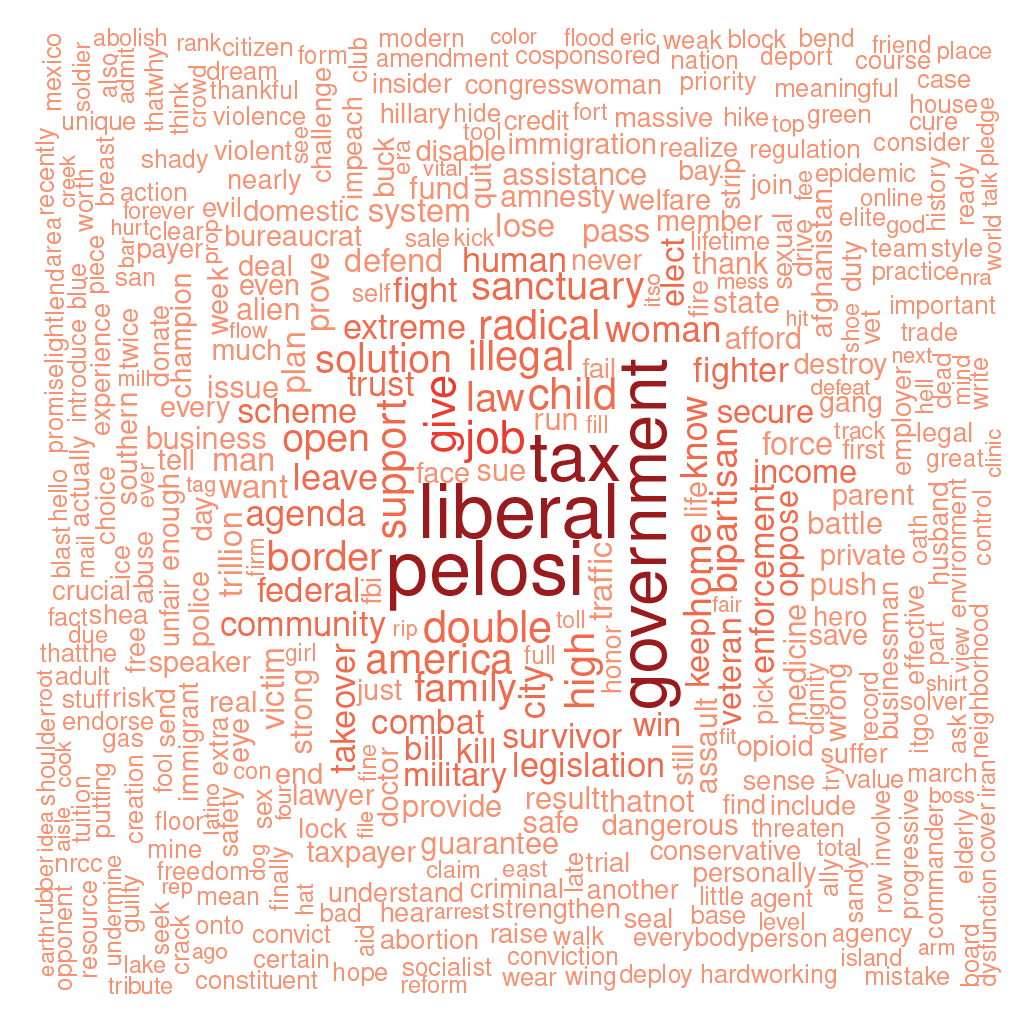

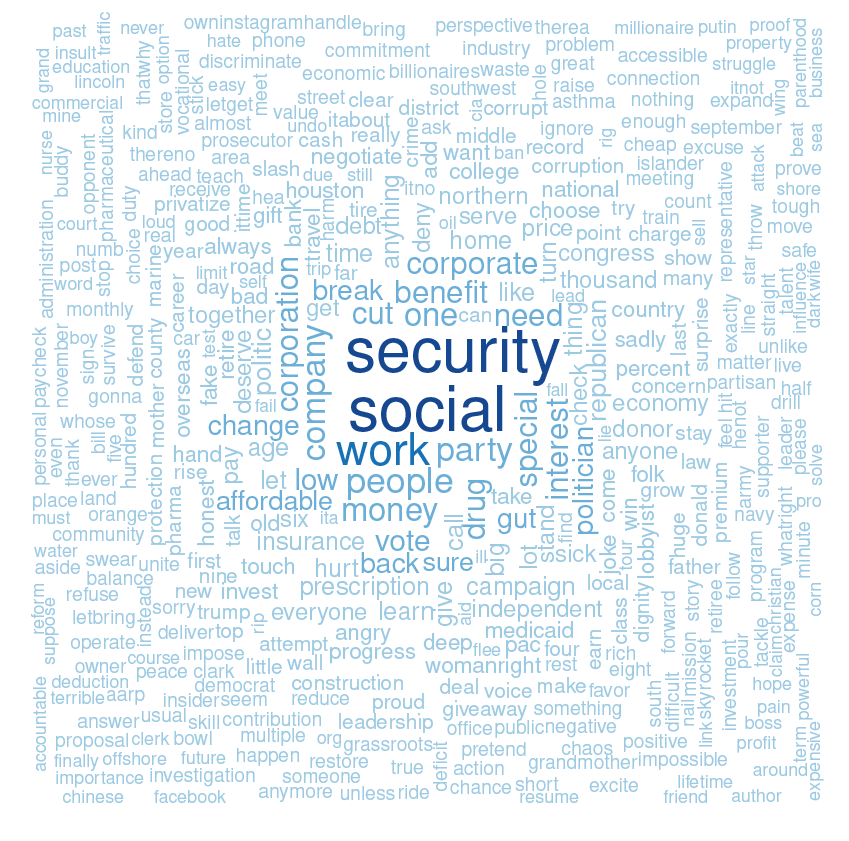

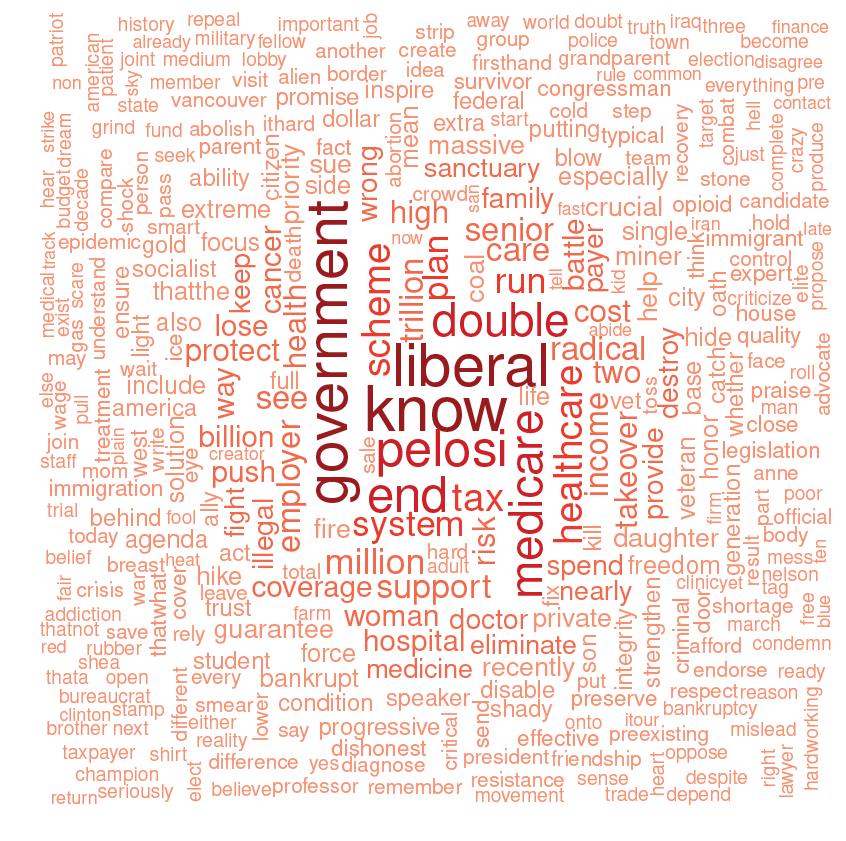

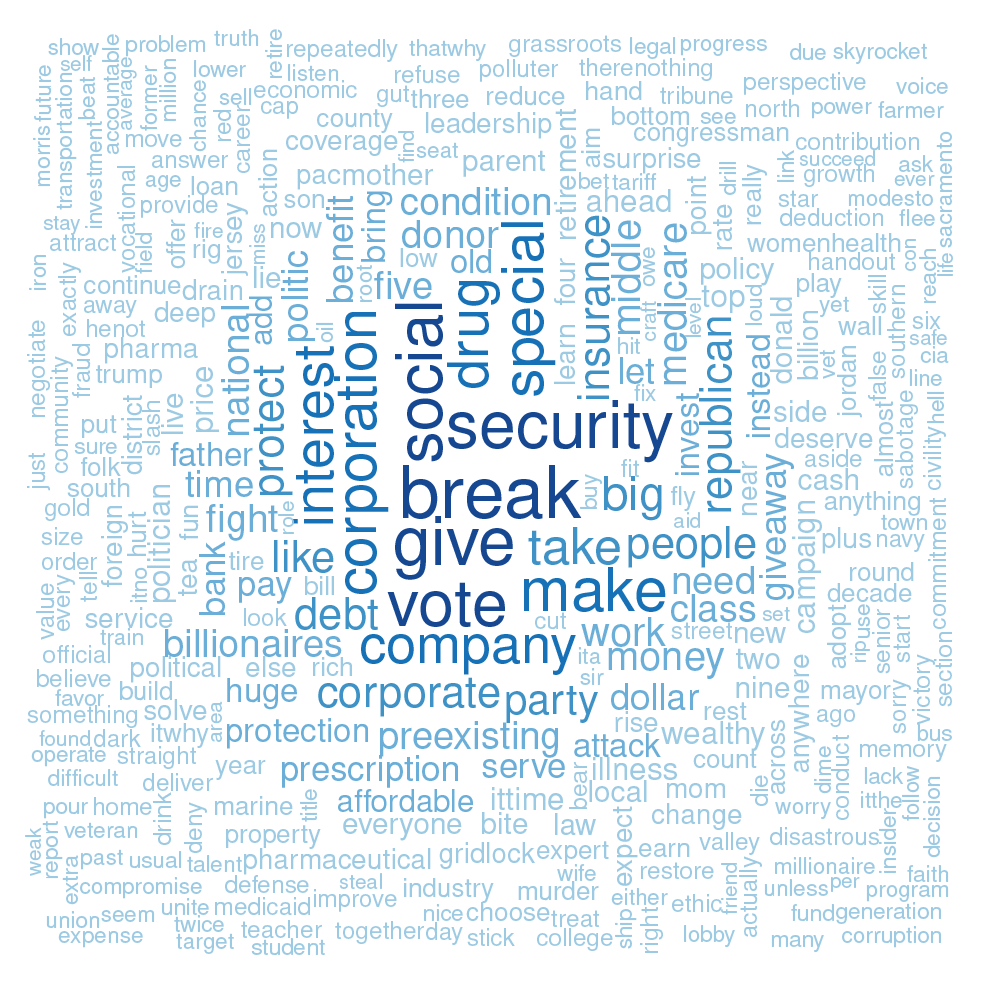

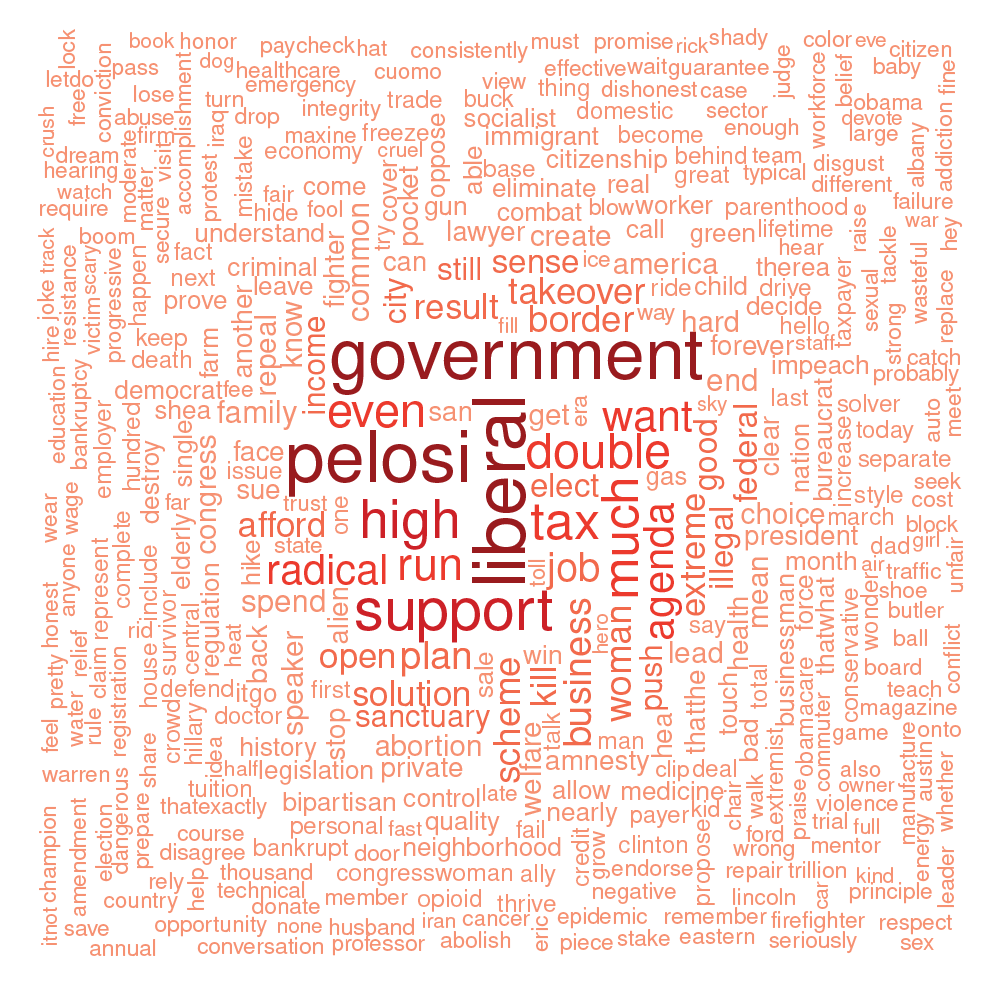

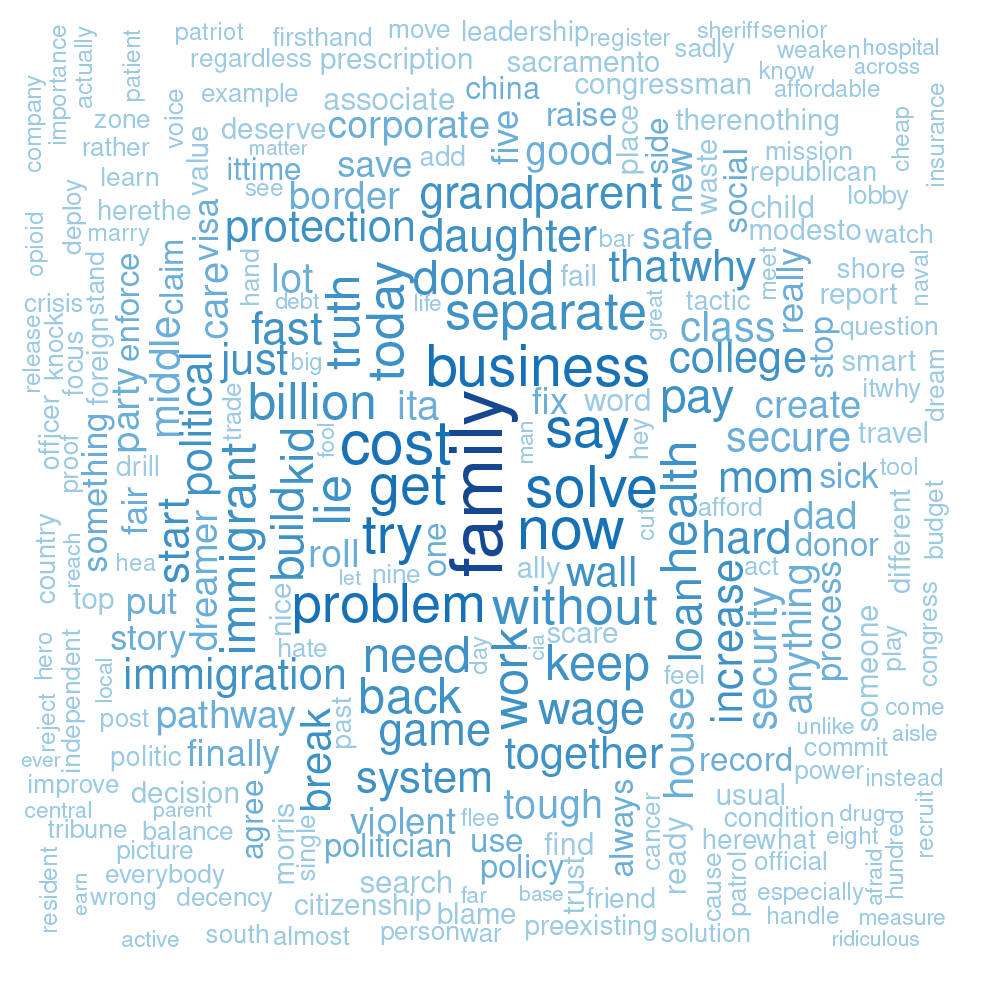

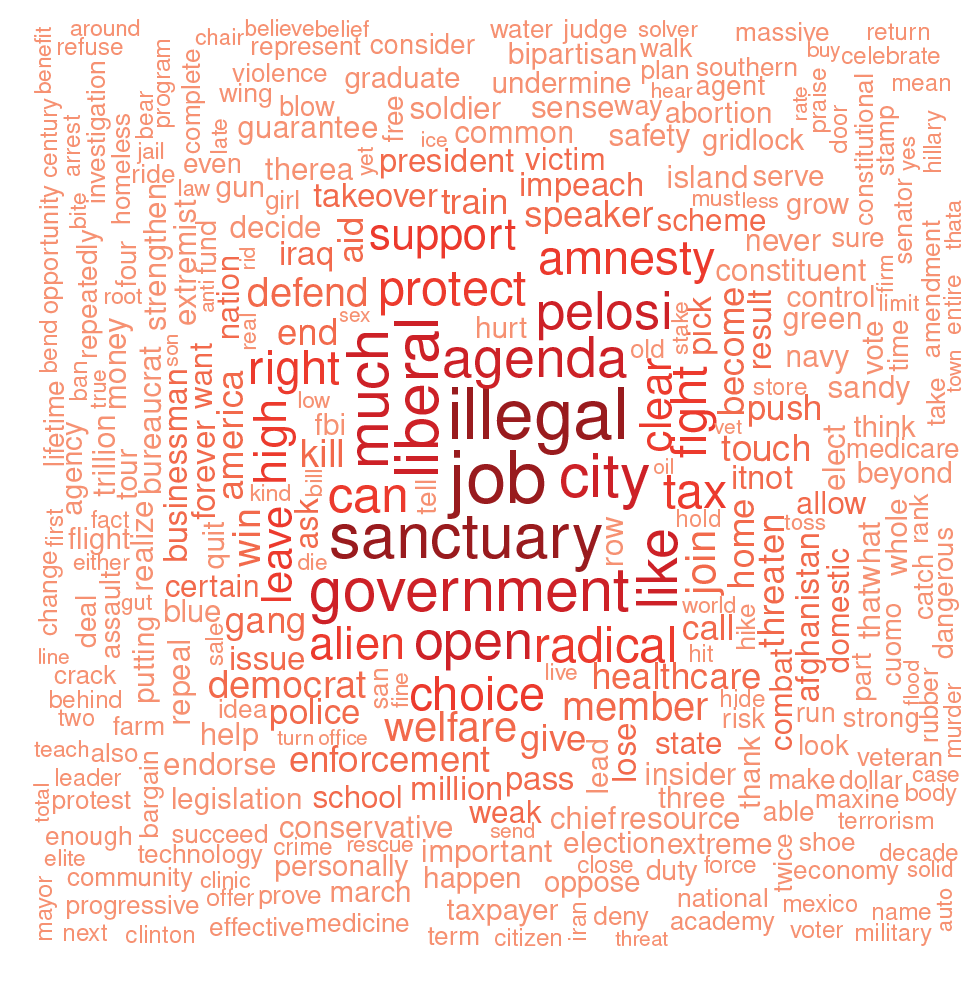

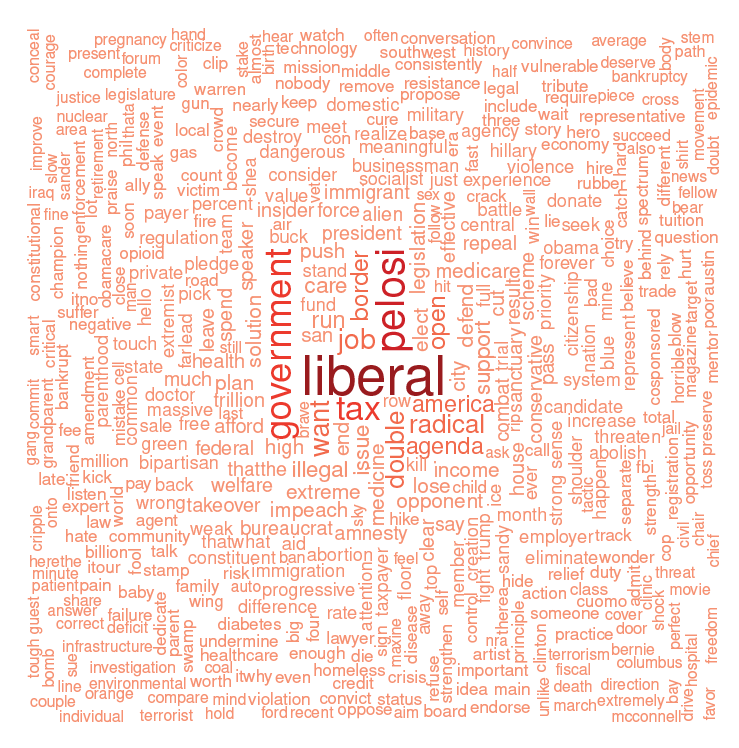

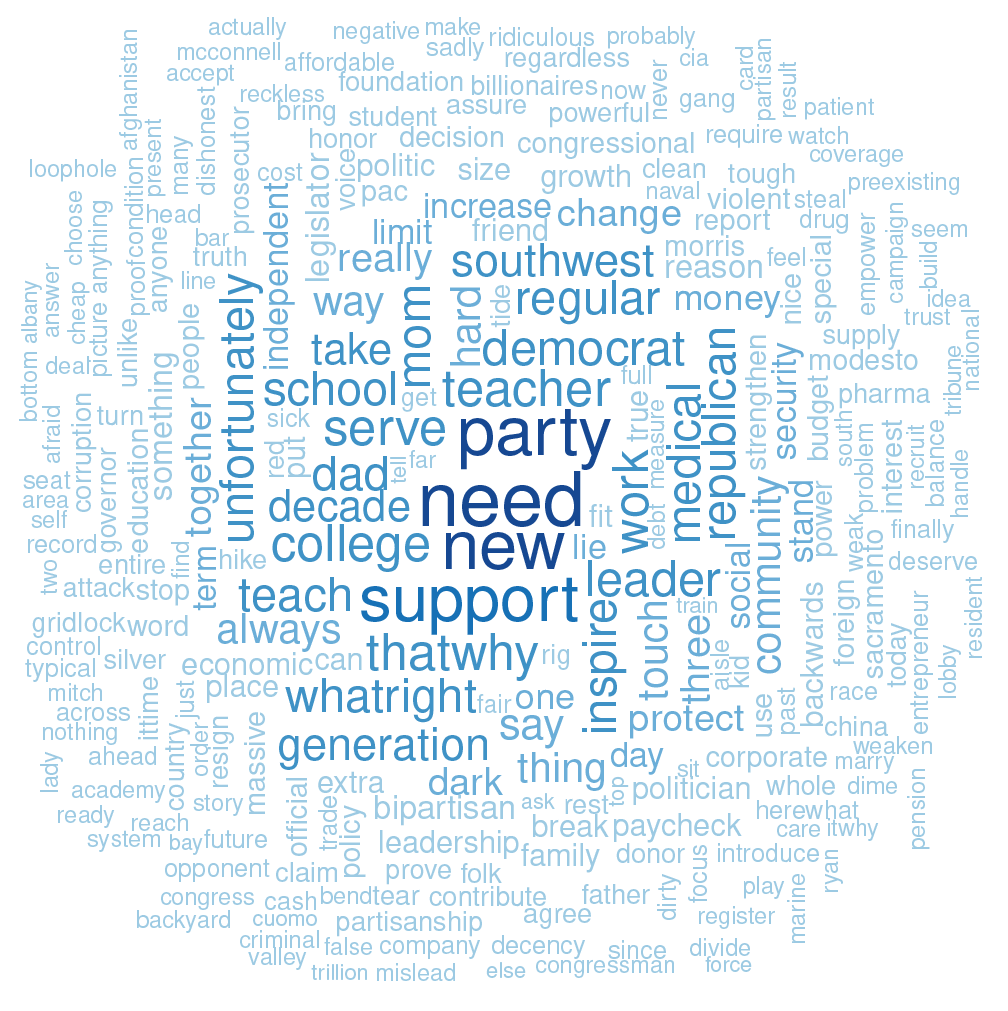

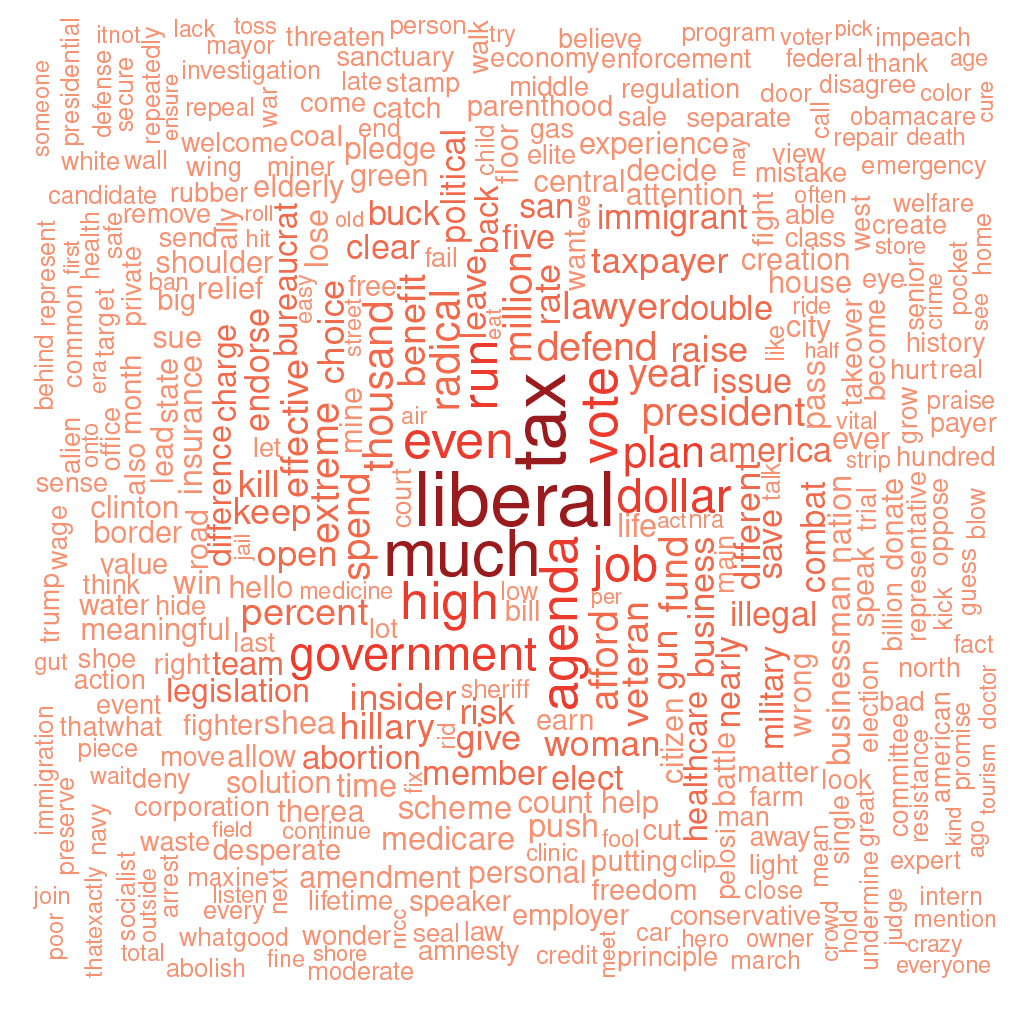

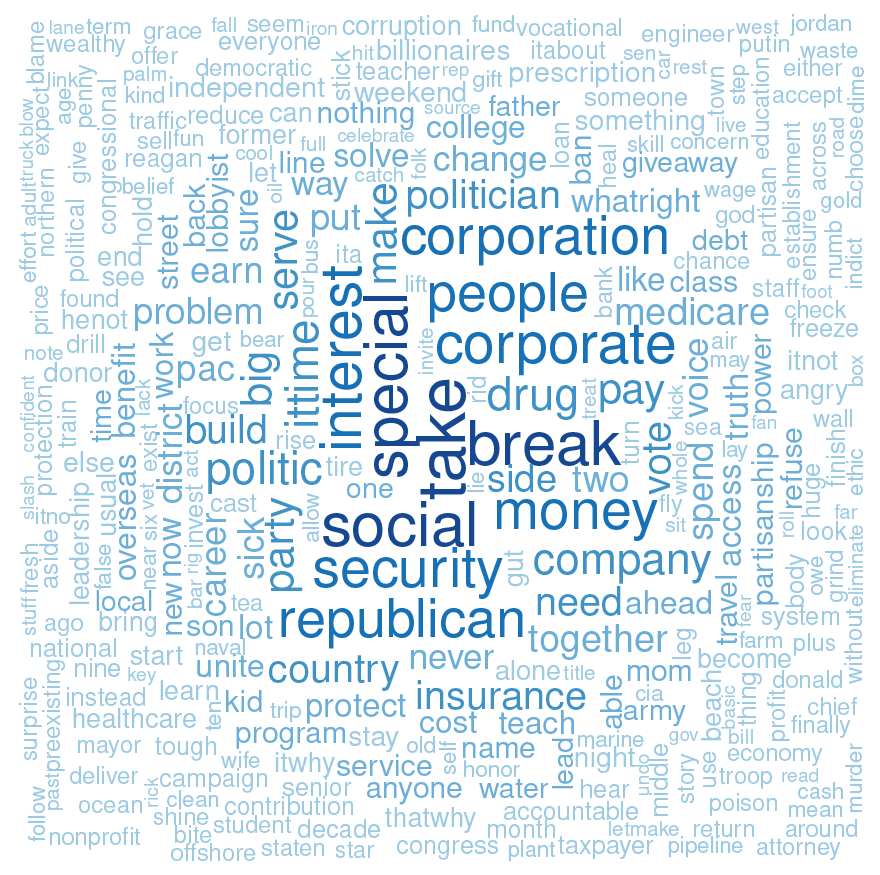

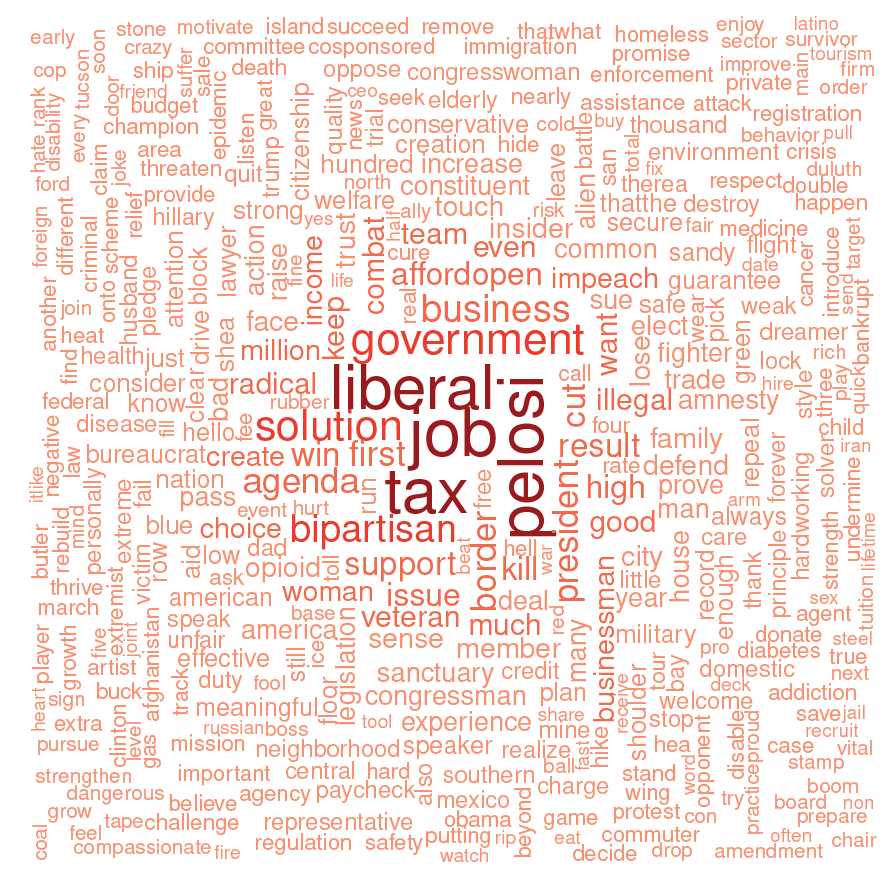

When we look at each side’s owned words—words that are disproportionately used by one party or the other—we can focus not just on the overall frequency of topics, but also their relative frequency. The word clouds below show the words that are most strongly associated with each party, based on their usage in campaign television ads.

Democrats focused overwhelmingly on making health care affordable and accessible—including protections for people with pre-existing conditions—and putting people ahead of corporations. By contrast, Republicans focused on negative and divisive rhetoric against “liberal” Nancy Pelosi, claimed Democrats would increase taxes, and stoked fear about the role of government—first and foremost a “government takeover of health care,” but also signaling broad opposition to “big government,” taxes, and regulation. The Democratic campaigns were focused mainly on the policy goals of Democratic candidates, while Republican campaigns were focused on making voters afraid of Democrats by tying them to the aforementioned issues.

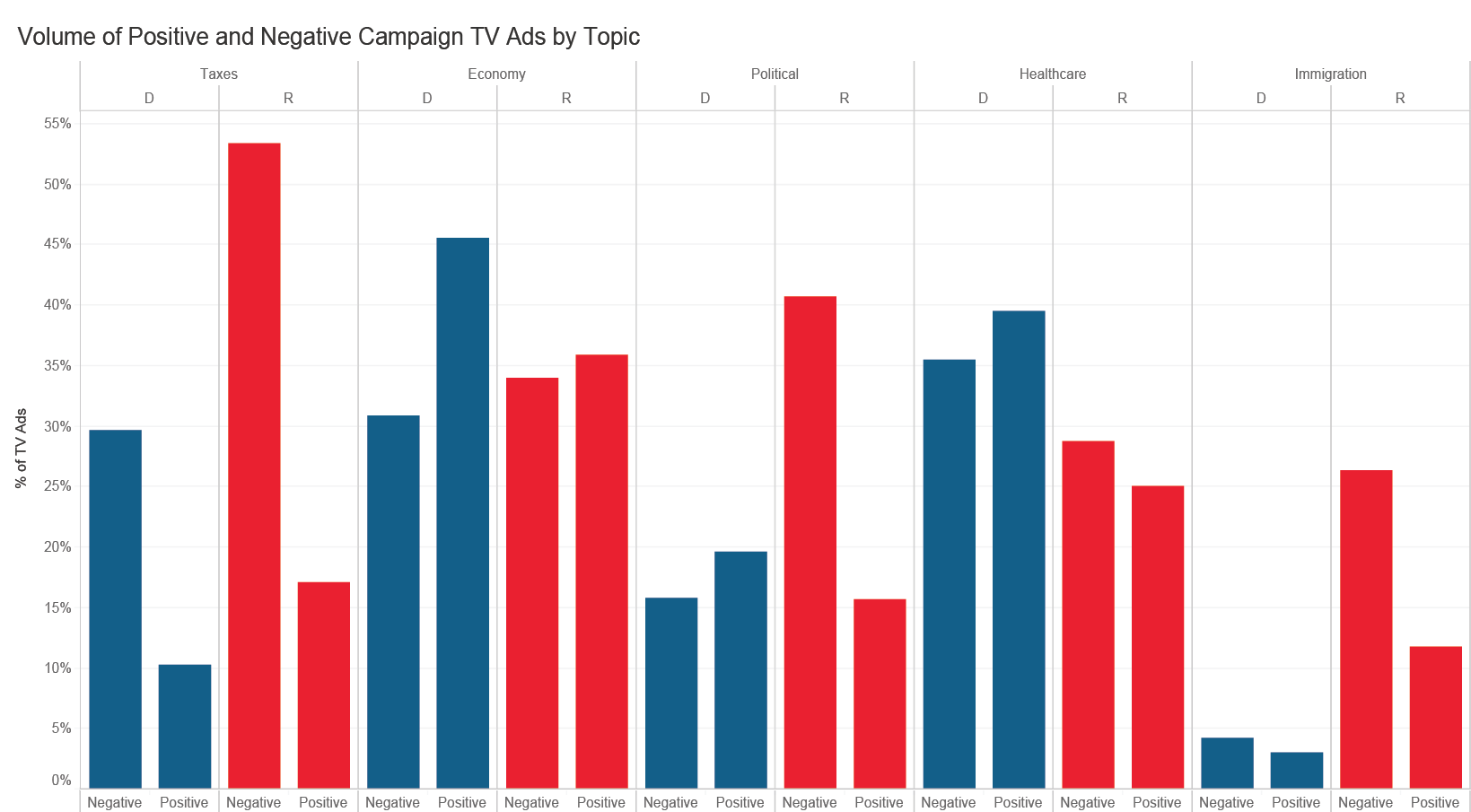

In addition to differences in content, there was a clear difference in tone. In television ads mentioning health care, immigration, partisan political terms, and taxes, Republicans were more likely to attack Democratic positions and policy initiatives. The only topic on which Republican campaigns ran more positive ads than negative ads was the economy, and only by a narrow margin. Democrats, by contrast, were more likely to run positive ads overall, except for when attacking the Republican position on taxes or immigration.

| Health Care

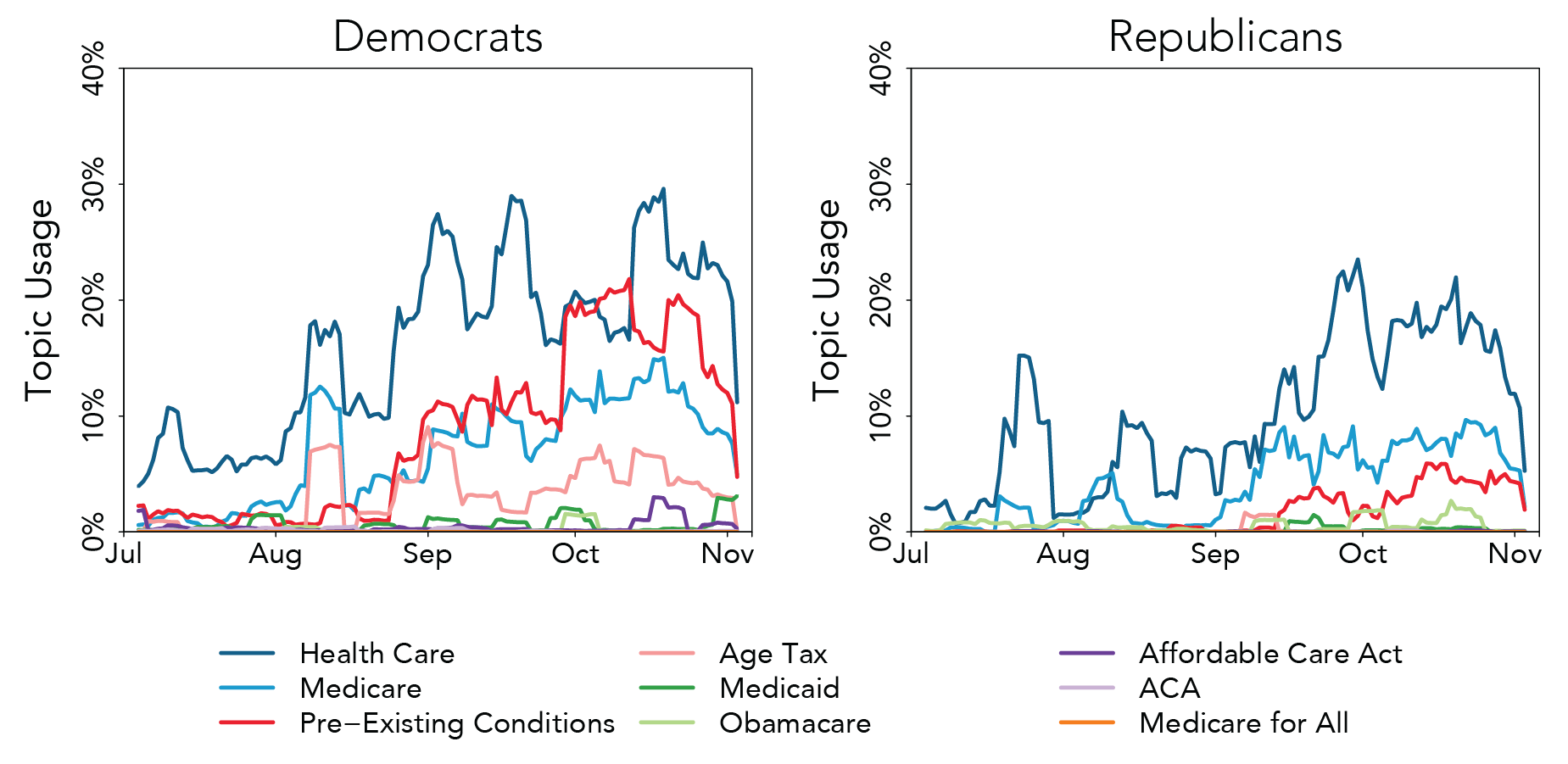

Reviewing health care discussions over time, we see that Democrats talked about the topic more than Republicans and “health care” (or “healthcare”) was itself the most frequently used term. The plot below shows a moving average of health care-related terms used in television ads, Facebook posts, and ads, or Tweets, with each document type given equal weight.

Topic Usage: Health Care

Democrats’ top health care-related issue was pre-existing conditions, followed closely by protecting Medicare. Democratic candidates increasingly referenced both topics from July through October.

Republicans avoided substantive discussions on health care, but as Democrats talked about these issues more, it seems they were pushed to engage—Republican mentions of health care, Medicare, and pre-existing conditions all spiked in the wake of increased Democratic usage of these terms.

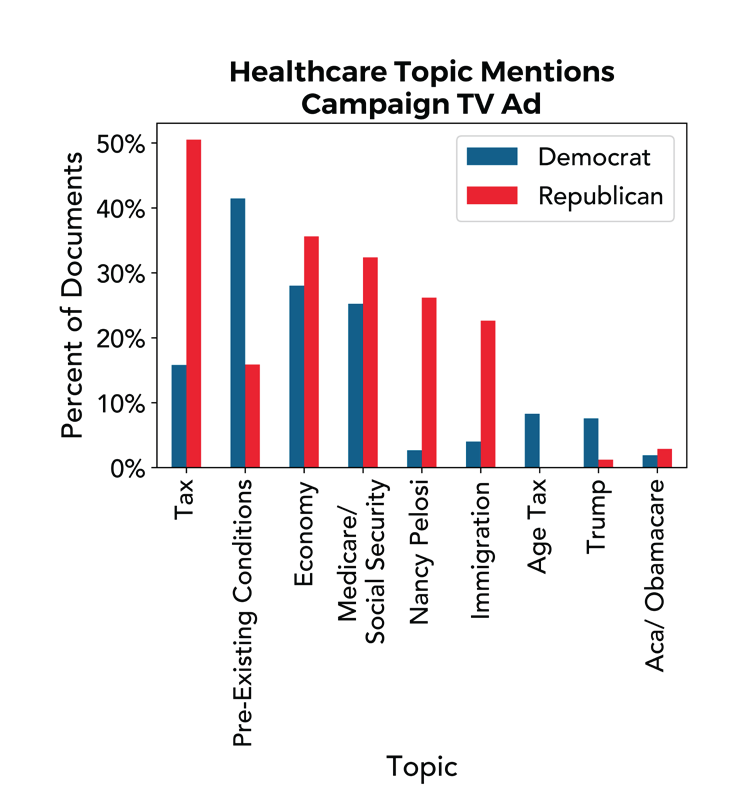

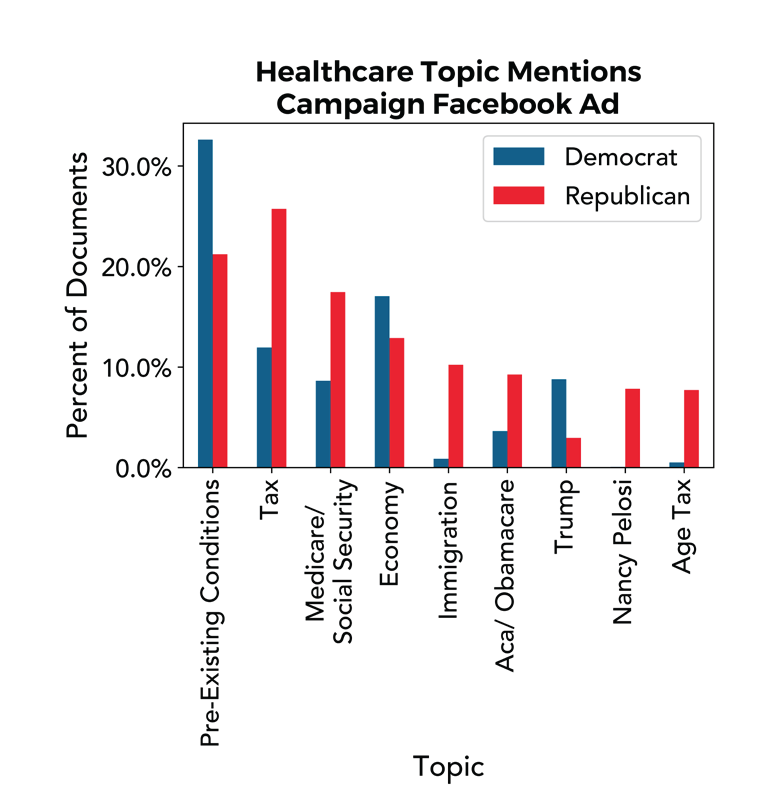

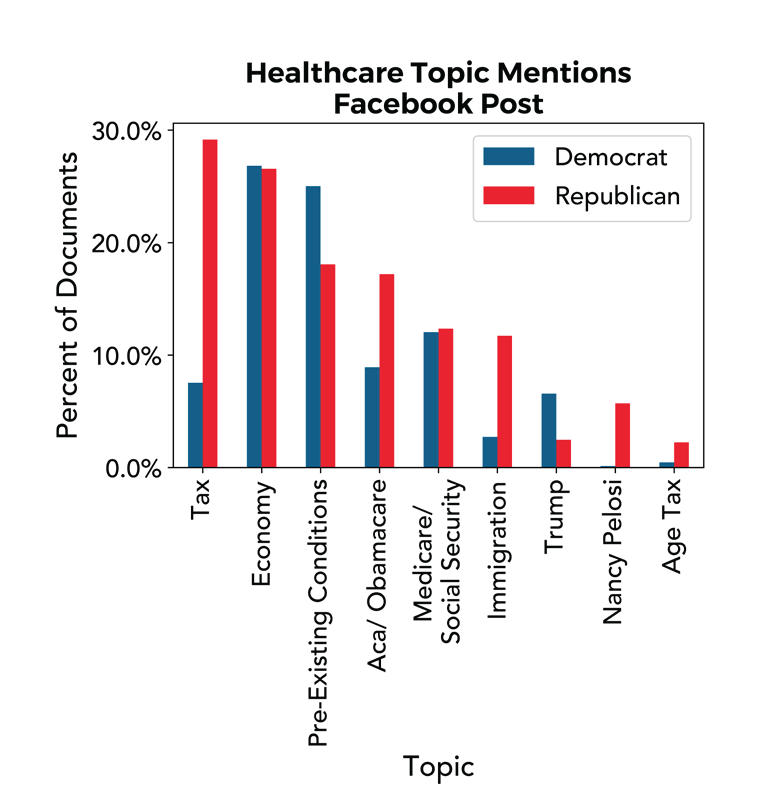

When we explore which other topics were raised in conjunction with health care, we see some clear partisan differences. The tables below show the frequency of topics that were mentioned along with health care in campaign messaging.

Republicans frequently talked about health care in the context of other issues—particularly taxes, the economy, and Medicare. Democrats consistently focused on pre-existing conditions and the need to protect people who would be denied insurance under Republican proposals. When talking about health care, Democrats steadily outpaced Republicans in mentions of protections for people with pre-existing conditions and prescription drug costs across all communication platforms except Twitter, where candidates from both parties discussed pre-existing conditions at the same rates among their health care-related Tweets.

Republicans were far more likely to frame any potential change in health care policy as a tax increase. They were also more likely to introduce unrelated bogeymen into the conversation, pivoting to attacks on Nancy Pelosi or to talking about immigration, which we will discuss further in the sections on Social Security & Medicare, Scapegoating Immigrants to Oppose Social Programs, and Partisan Political Terms.

In addition to comparisons between Democrats and Republicans, we also examined differences within parties. Understanding intra-party differences may help us understand the electoral battlefields in different parts of the country and provide greater understanding ahead of the next presidential election.

On the topic of health care, we found marginal to no difference across a number of candidate or congressional district traits: candidate race, majority-minority (a district where one or more racial and/or ethnic minorities—relative to the whole country’s population—make up a majority of the local population) compared to majority-white districts, or urban, suburban, and rural districts. Differences were pronounced when we examined markers for the competitiveness of the district: Cook rating, incumbency, and 2012-2016 vote history.

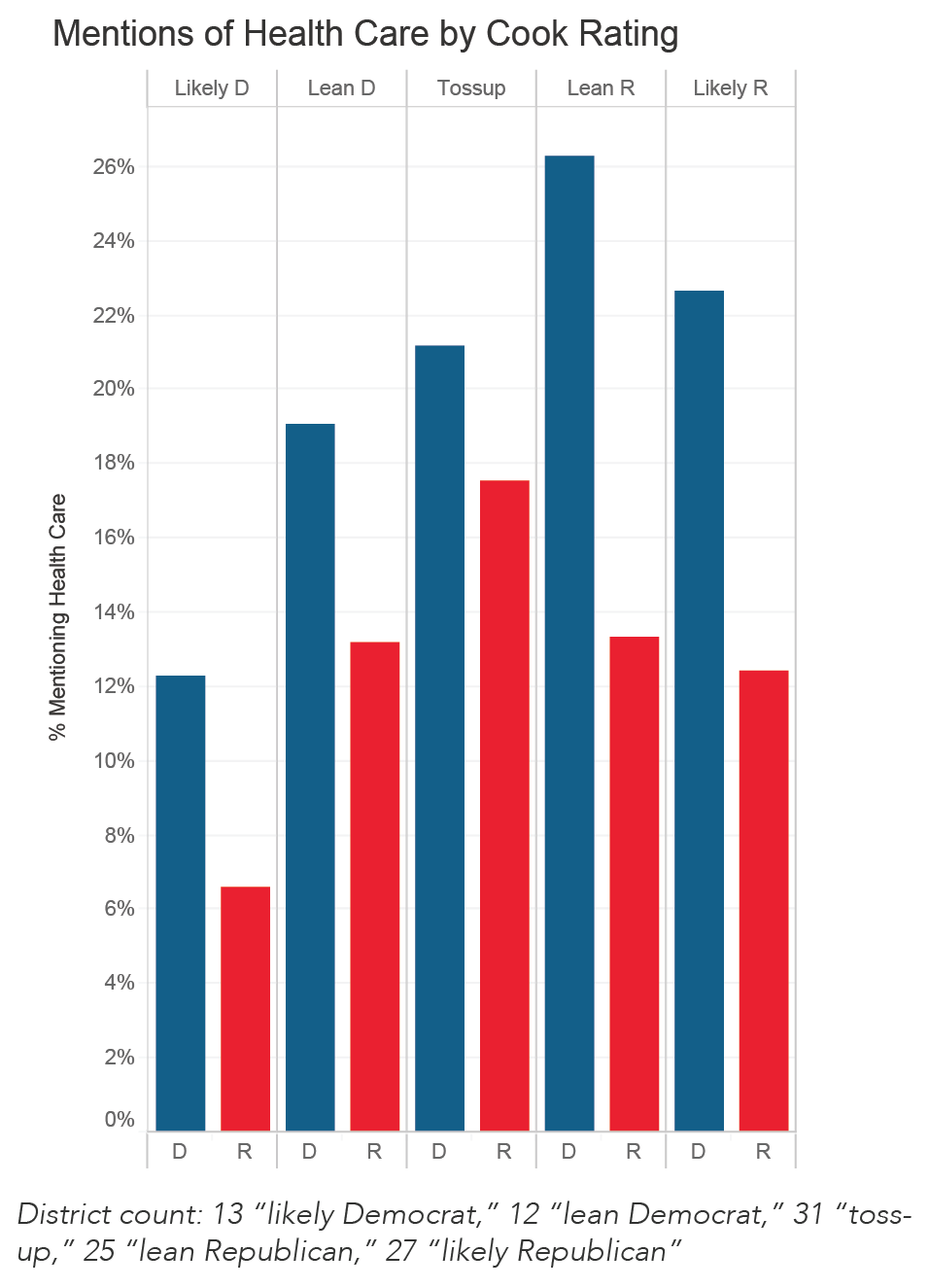

Democrats talked about health care most in “lean Republican” districts, followed by “toss-up,” and “likely Republican” districts, and least in “likely Democratic” districts. They also emphasized health care most in incumbent Republican districts and least in incumbent Democratic districts, which likely reflects the battlefield of competitive districts with vulnerable incumbents or candidates who chose not to run for re-election. Democrats talked about health care most where Republicans were most likely to win (districts characterized as “likely Republican” and “lean Republican” by Cook Political Report), possibly viewing the issue as one that would resonate with the most persuadable voters. On the flip side, Republicans talked about health care less in incumbent Democratic districts than anywhere else.

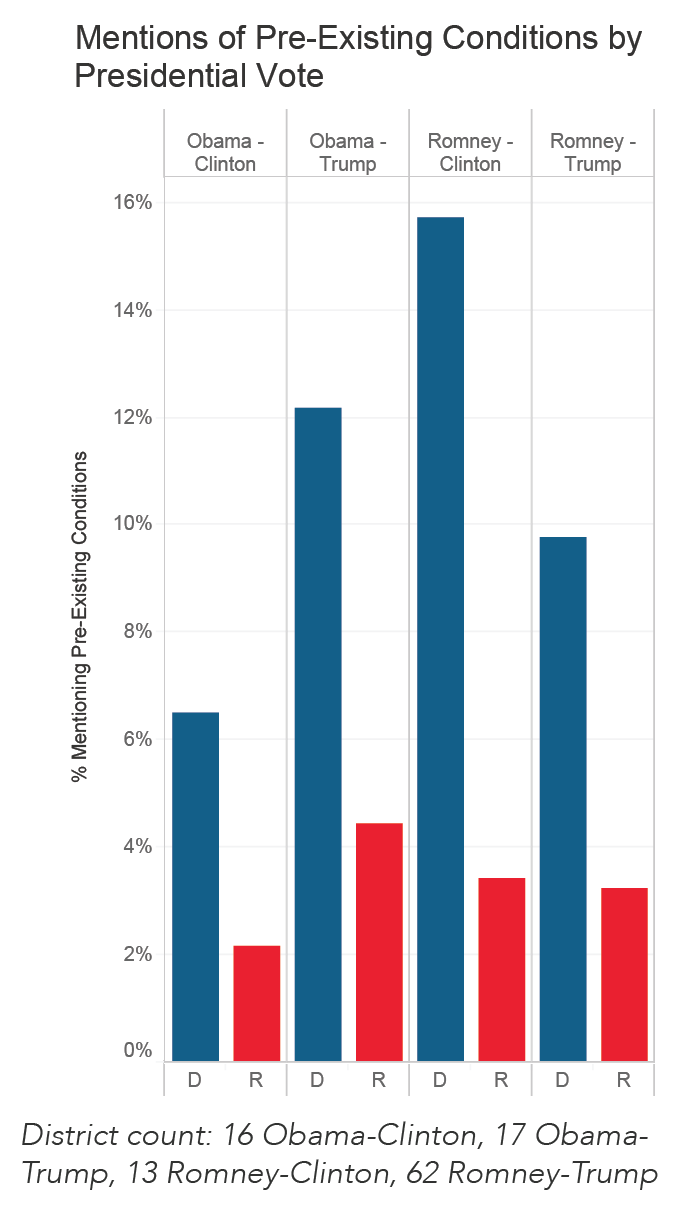

Democrats were also most likely to talk about health care in congressional districts that voted for Obama in 2012 and Trump in 2016 (“Obama-Trump” districts), potentially viewing this as a motivating issue for party-switching voters.

| Pre-Existing Conditions

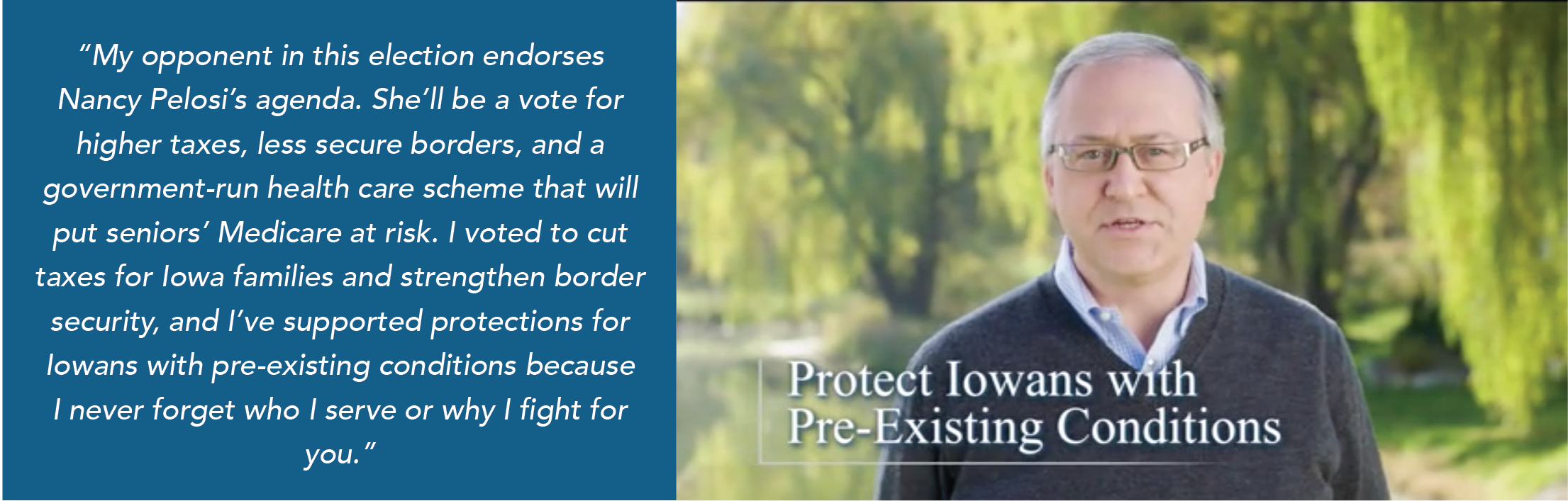

Republican communications on pre-existing conditions were largely defensive and lacking in substance. Republicans used a few common patterns to address the issue: accusing their Democratic opponent of lying and then asserting he or she has always supported coverage for pre-existing conditions; declaring he or she supports coverage for pre-existing conditions, with no further argument to substantiate their stance on the issue; referencing how a pre-existing condition has impacted a close family member, or pivoting to talk about the Affordable Care Act raising rates.

As the word clouds below suggest, Democrats were talking about pre-existing conditions in the context of real issues: ensuring protections for people in need, the role of insurance companies, and the necessity of affordable drug coverage. Republicans, on the other hand, warned of a “big government takeover of health care” and an end to “Medicare as we know it,” without providing more detail for their assertions.

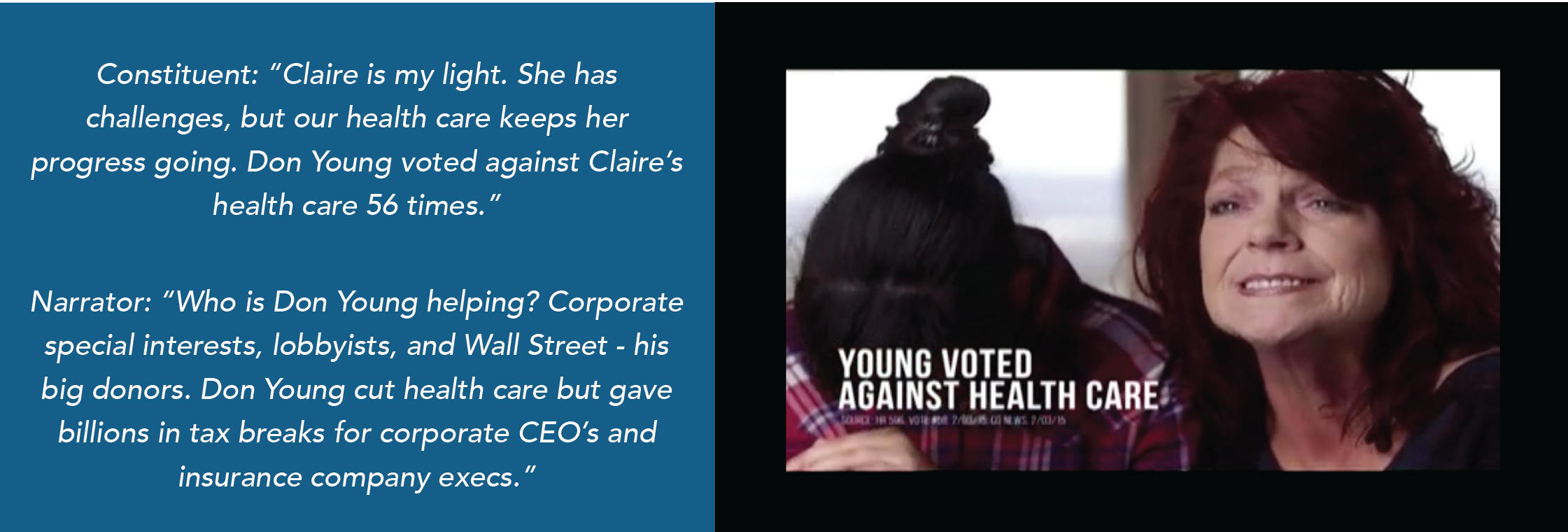

A campaign-sponsored television ad supporting David Young (IA-03) encapsulates the Republican approach:

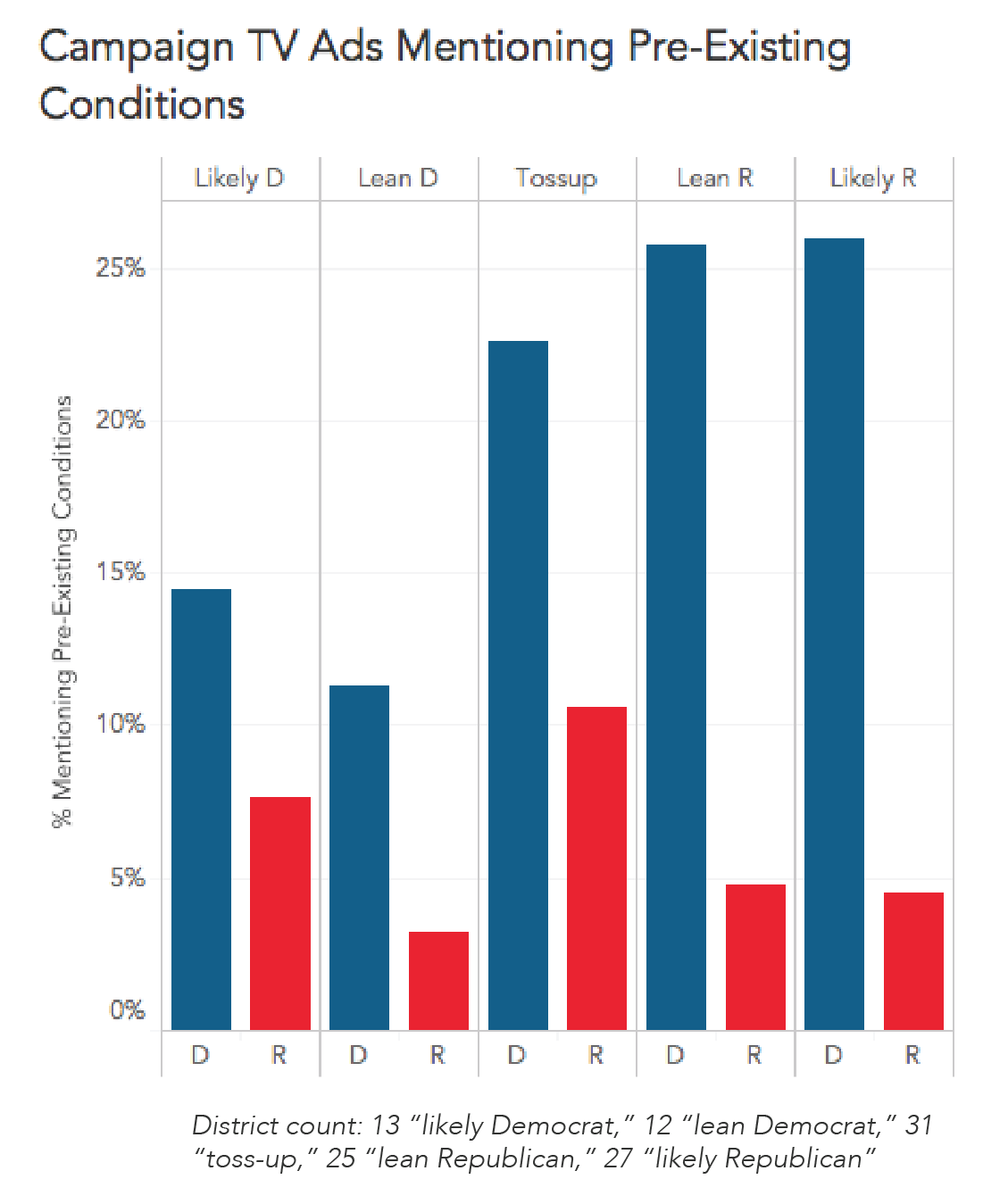

Intra-party differences arise on the topic of pre-existing conditions. Examining topic usage by district competitiveness as measured by the ratings from Cook Political Report, we see that Democrats clearly viewed pre-existing conditions as a winning issue, mentioning it most often in the toughest contests (districts labeled as “toss-up,” “lean Republican” or “likely Republican”). Republicans, by contrast, mentioned pre-existing conditions in less than eight percent of ads in all kinds of districts, except for the most competitive districts, where the term was used marginally more (10.4 percent of the time).

Among Democrats, female candidates focused more on pre-existing conditions than male candidates. The plot below shows a moving average of the prevalence of the topic over time in Facebook ads by gender.

From Labor Day onward, when the campaign was in full swing, there was a large gap in the emphasis on pre-existing conditions between Democratic women and everyone else. This gap shrunk dramatically at the end of September and the beginning of October, during the second round of then-Judge Kavanaugh’s confirmation hearing to the Supreme Court, and then returned to higher levels for the rest of the cycle.

Interestingly, Democratic women made pre-existing conditions their closing issue in Facebook ads, and Republican women ramped up their usage of the topic during the final stretch as well. By contrast, men on both sides of the aisle maintained their existing strategy in the final weeks of the election.

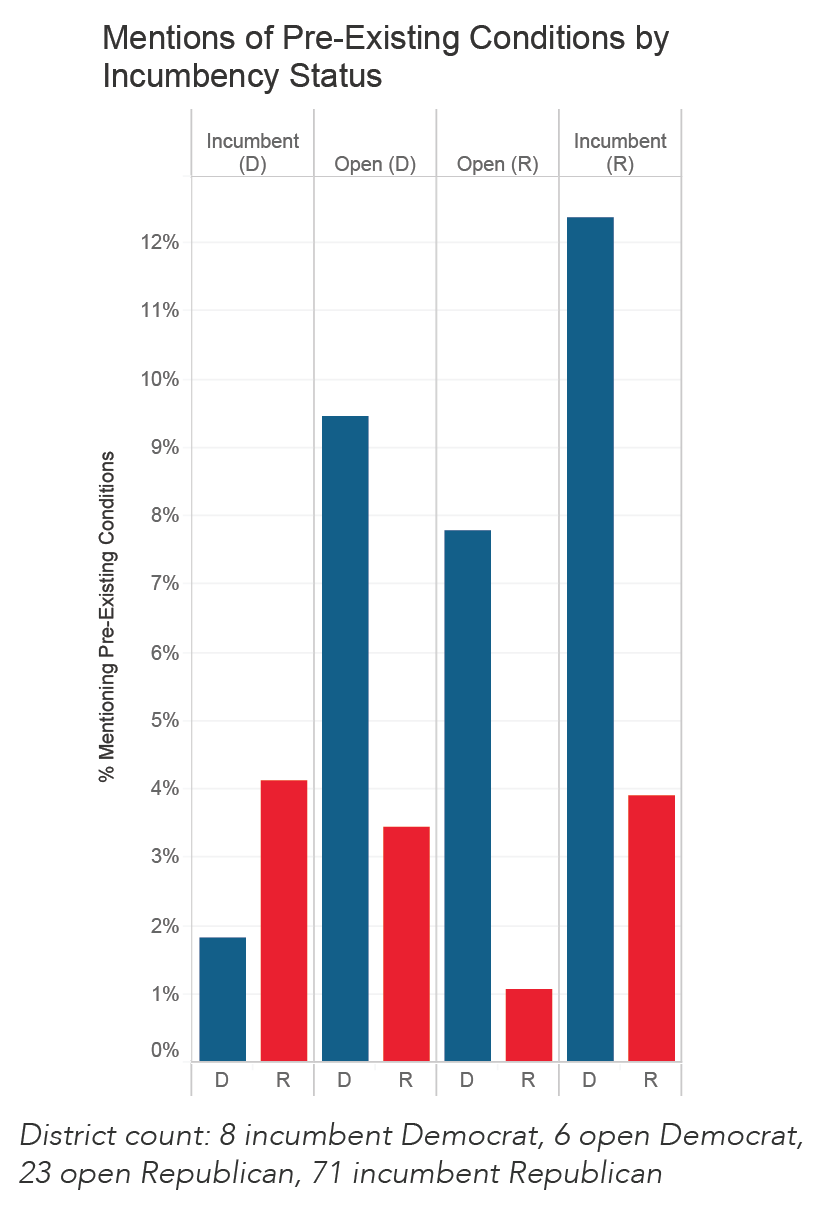

Democrats discussed pre-existing conditions the most in districts that leaned Republican: those that voted for Romney in 2012 then Clinton in 2016 and districts with a Republican incumbent.

| Social Security & Medicare

Social Security & Medicare are commonly viewed as critically important issues for older voters, as both programs help populations across the country maintain their quality of life. The word clouds on the right illustrate how the parties’ rhetoric on Social Security and Medicare differ. We observed that the Democrats’ message centered around protecting funding for Social Security and Medicare, ensuring affordable access to health care and prescription drugs, and not putting corporations or drug companies ahead of people. Republicans’ messaging focused, again, on big government, “liberals,” Nancy Pelosi, and the argument that Democratic policies will “double taxes” and “end Medicare.”

In television ads, Republicans portrayed the 2018 election as a choice between two issue groups: Social Security, “Medicare as we know it,” and free market-driven quality health care on the one hand, and a “government takeover of health care” that would raise premiums, raise taxes, raise the deficit, or put the future of Medicare in jeopardy on the other. Again, Republicans relied on fear, threatening that seniors will lose Social Security and access to quality health care if Democrats won control of the House of Representatives.

For example, the following campaign-sponsored television ad for Republican John Faso (NY-19) portrays expansion of government programs for health care as a threat to Social Security and Medicare:

By contrast, Democrats argue Republicans’ tax breaks for millionaires and big corporations raise the deficit, threatening funding for programs like Social Security and Medicare. This campaign-sponsored television ad for Democrat Steven Horsford (NV-04) ties Republican tax cuts to threats to Social Security and Medicare:

| Scapegoating Immigrants to Oppose Programs

Republicans framed popular, Democratic-supported social programs as giveaways to “illegal immigrants.” This recurring theme enabled Republicans to pivot from their vision for cutting social programs by setting up a false dichotomy between social programs and immigration. A preliminary review of election outcomes suggests Republicans who put more emphasis on immigration did no better than their colleagues who avoided the topic—in other words, their base appeal to nativism did not increase their chances of victory.

We observed that Republican candidates fanned hatred and fear of immigrants and used this as a uniting threat for their base. They argued that the government should not offer the types of social service programs supported by Democrats, like the Affordable Care Act, because there is a chance that “illegal immigrants” might benefit at the expense of their constituents.

For example, this PAC-funded attack television ad by the Congressional Leadership Fund (a Republican group) against Democrat Anthony Brindisi (NY-19) pitted veterans against “government-run health care” for “illegal immigrants”:

Whether talking about undocumented immigrants or Medicare and Social Security, Republicans developed a line of attack that portrayed a false choice motivated by fear.

| Taxes

The Republicans’ signature tax law passed in 2017 was expected to be a central winning issue for Republicans to use in campaign communications going into this election, but it proved to be a polarizing and murky topic. Republicans argued that the tax law provided a tax cut for small businesses and the middle class, while Democrats argued that the same tax law was actually a tax cut for billionaires and big corporations that increased the federal deficit by $1.9 trillion.

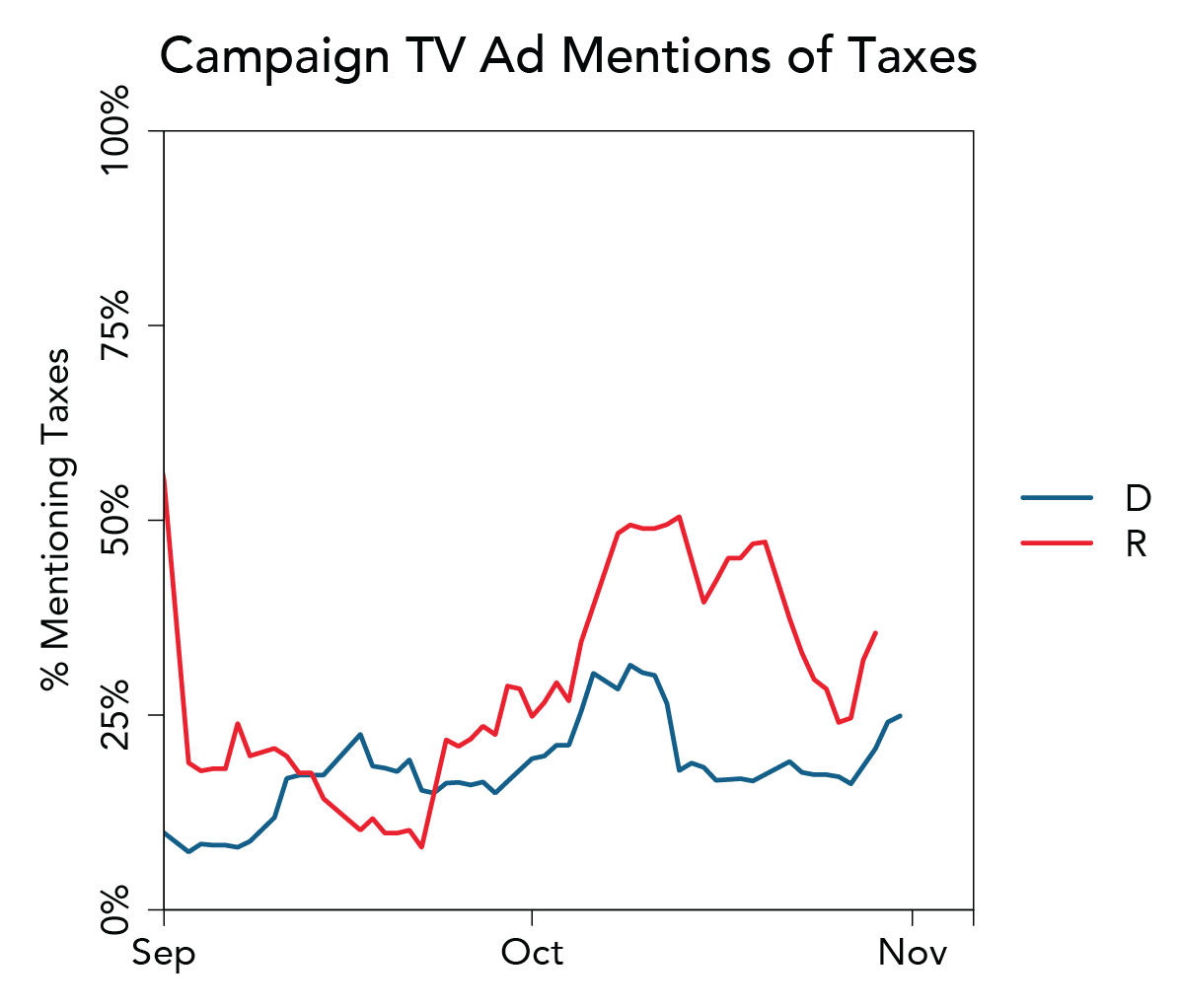

Republican communications on taxes peaked in mid-October then quickly declined in the final two weeks of the election. Despite expectations at the time the tax law was passed that it would help Republicans win during the 2018 midterms, the party did not make tax cuts their closing argument, instead focusing on immigration as Election Day approached.

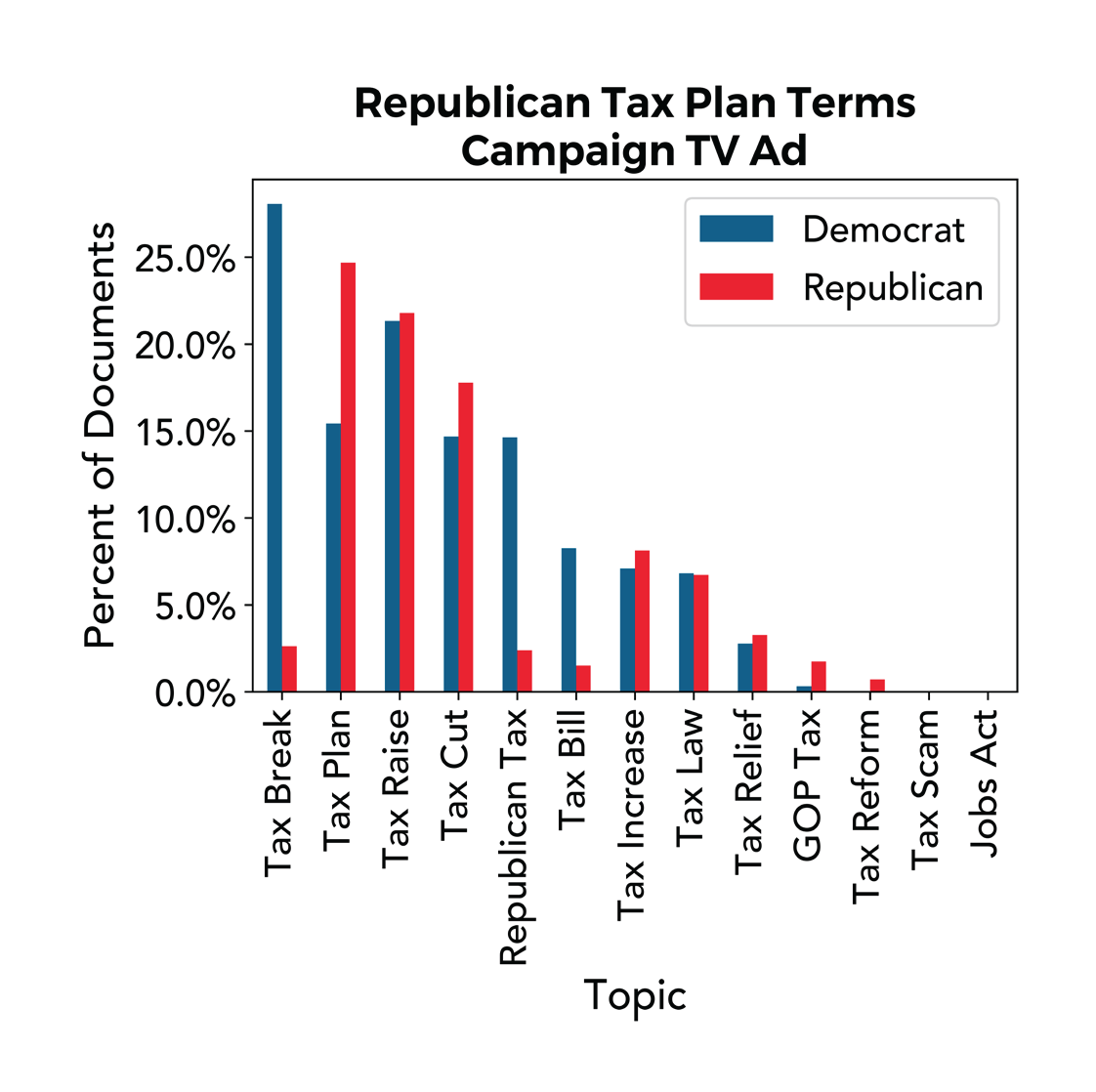

Examining the terms both parties used when talking about taxes in television ads, we saw both parties refer to a “GOP tax” plan, though Democrats used the phrase more frequently. Democrats were much more likely to use the phrase “tax break” with a negative connotation (e.g., “tax breaks to billionaires and corporations” or “tax breaks for the top one percent”), the “Republican tax” plan, or the “tax bill.” Republicans were more likely to talk about “tax cuts.”

Both parties talked about tax raises but in different ways. Republicans consistently accused Democrats of planning to raise taxes, while Democrats argued the Republican tax plan would raise middle-class taxes or force a cut in public programs. Polling conducted by Navigator Research in August 2018 has found the tax law to be net unpopular, and Americans are divided on which party to trust on the issue of taxes—a notable change from a historical advantage Republicans have held until recently.

When discussing their signature policy, Republicans were likely to refer to it as “tax cuts,” rarely using the name of the bill, “Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.” In fact, the phrase “Jobs Act” did not show up once in our television ad data, although the phrase was used on social media, appearing in seven percent of Republican Tweets about taxes, 10 percent of their Facebook posts, 12 percent of Instagram posts, and three percent of Facebook ads.

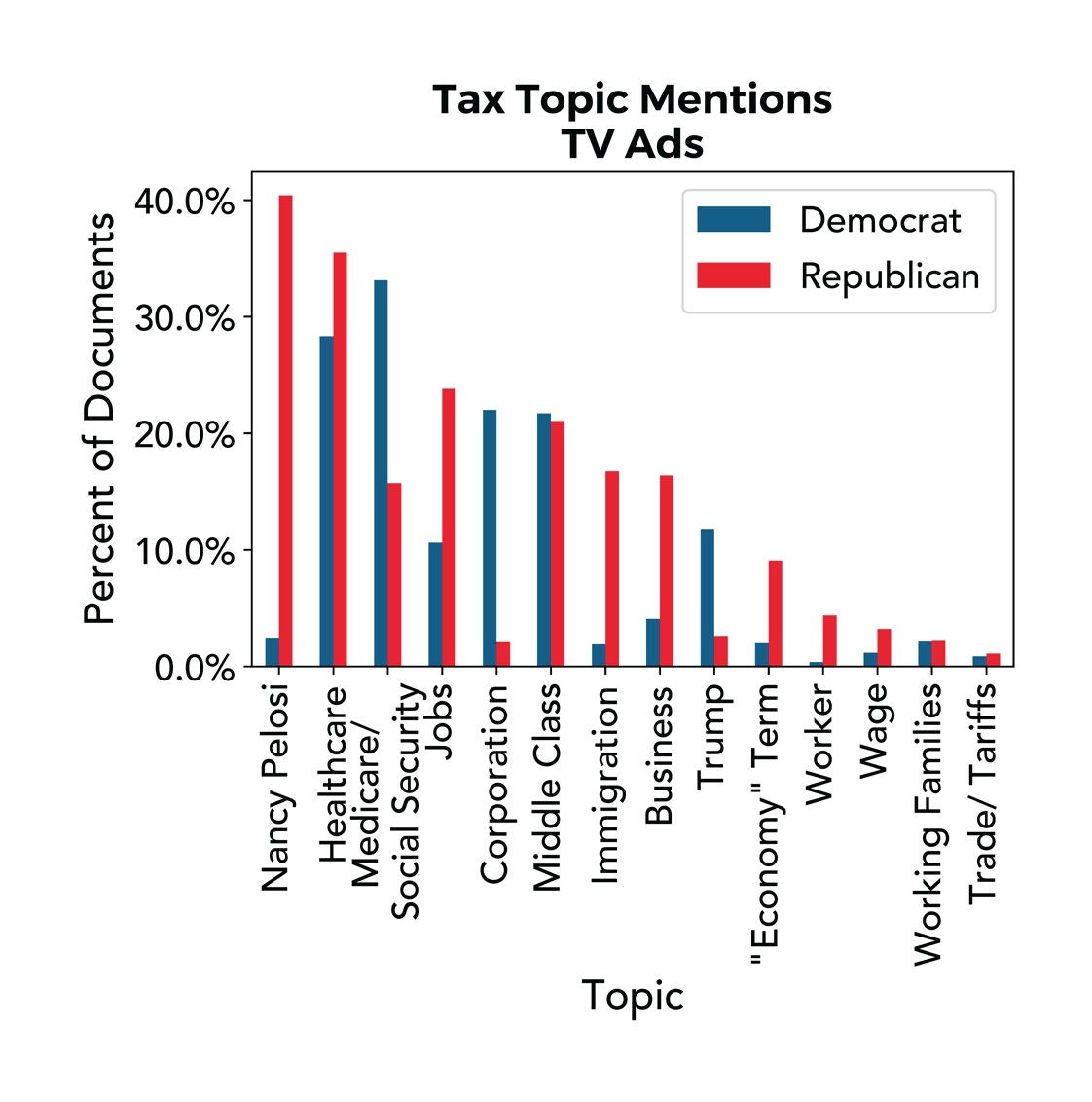

Democrats tended to frame the tax law as beneficial to the wealthy and large corporations at the expense of the middle class, increasing the deficit, and threatening programs like Social Security and Medicare. Republicans framed the tax law as a benefit for families and businesses (frequently emphasizing the child tax credit) and threatened that Nancy Pelosi would raise taxes if she becomes Speaker.

Looking at television ads that mention taxes, we see that Republicans ran on a negative, anti-Pelosi message first and foremost, rather than a positive message that emphasized their record over the past two years or a constructive vision for the future. Even on an issue for which Republicans have a clear legislative record, they largely spent their energy stoking fear about what Democrats would do instead if they gained control of the House of Representatives. In Republican campaign and PAC television ads that mention taxes, 40 percent mention Nancy Pelosi and 35 percent mention health care (arguing that Democratic health care plans will increase taxes). By contrast, Democrats focused on Medicare, Social Security, and health care while discussing taxes.

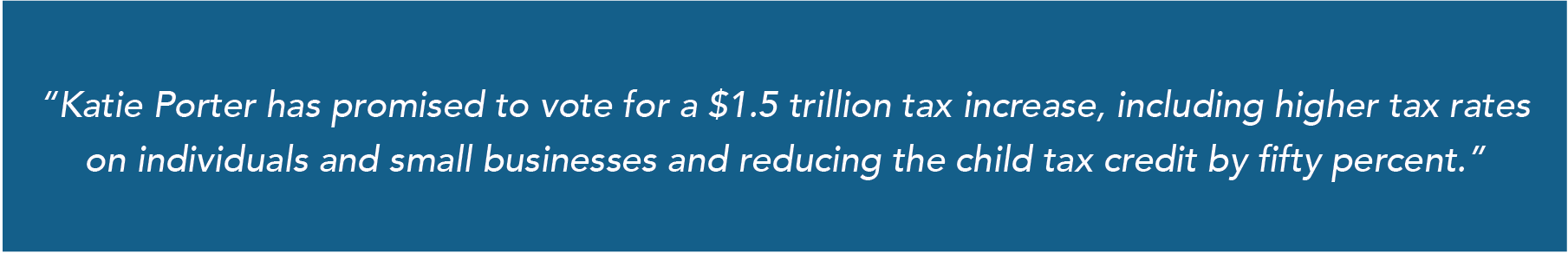

The National Republican Campaign Committee’s (NRCC) website for opposition research provided talking points that epitomized the Republican position. For example, they attacked Katie Porter (CA-45), saying:

Democrats, by contrast, focused on the beneficiaries and victims of Republican tax policy. This ad from Alyse Galvin, the Democrat-aligned Independent candidate for Alaska’s at-large seat, exemplified the approach from the left:

When we look at owned words related to taxes, the same themes emerge again, seen in the word clouds below.

The word clouds on the previous page show that Democrats were hammering the message that the GOP tax breaks are a giveaway to corporations, billionaires, and special interests, threatening Social Security and Medicare. Republicans, but contrast, ran on anti-government, anti-liberal, and anti-Pelosi sentiments. Considering the tax law is Republicans’ major legislative victory of the past two years, they had surprisingly few positive or substantive talking points to promote.

We did not find substantial intraparty differences on taxes from Democrats, but there were a few noteworthy dimensions among Republicans. Republicans were far more likely to discuss taxes in suburban areas, followed by rural areas. Republican mentions of taxes in denser districts were roughly on par with those of Democrats. Republicans were more likely to discuss taxes in districts carried by Mitt Romney in 2012, particularly if those districts also voted for Donald Trump in 2016. This suggests that Republicans viewed taxes as a favorable issue for rallying their base and for motivating the suburban voters who helped swing the 2016 election. Republicans were less likely to mention taxes in majority-minority districts, though that may be less a function of the issue itself and more a function of the fact that Republicans in those districts had to find novel talking points in order to present themselves as distinct from the national party.

| Immigration

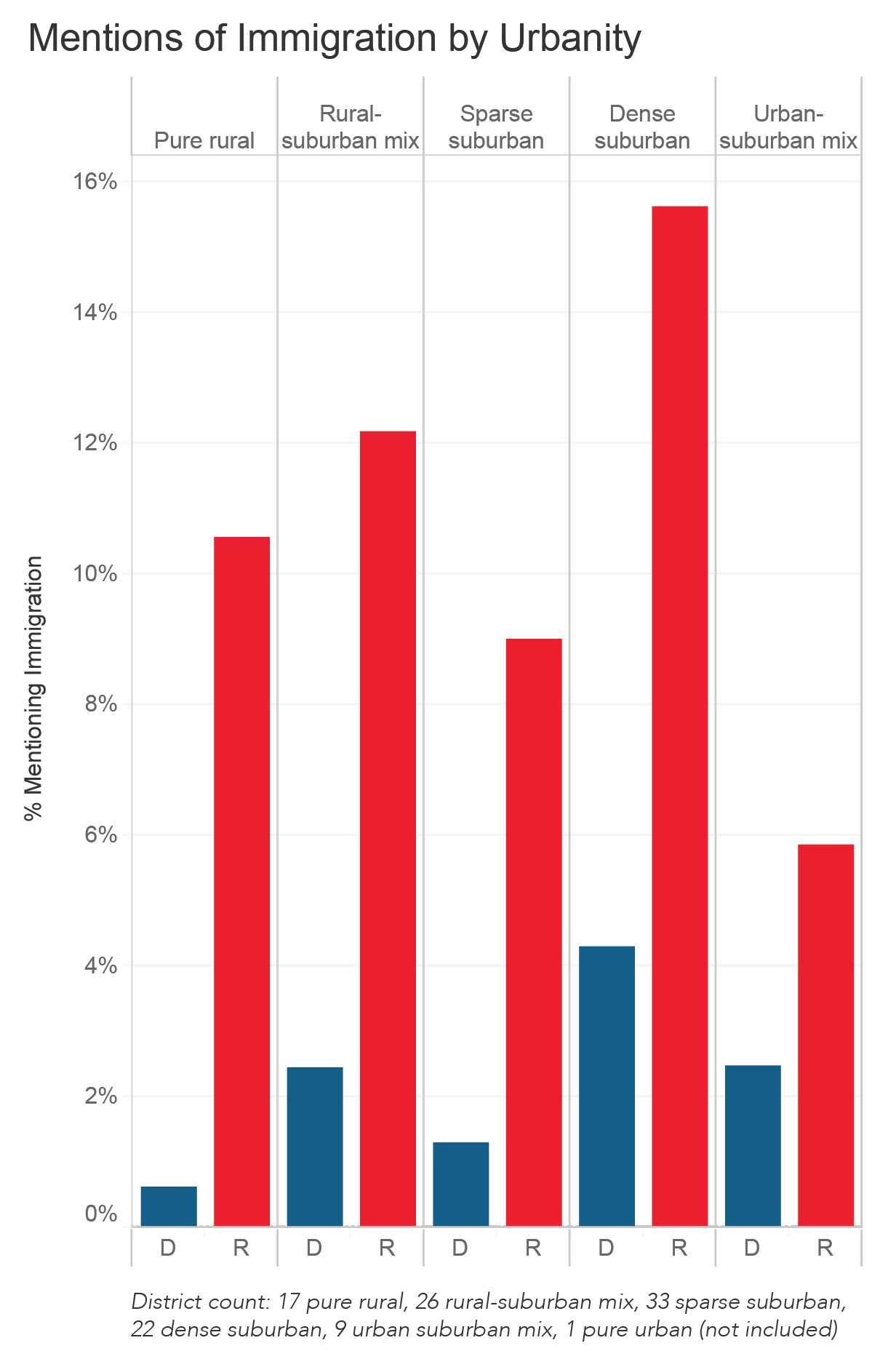

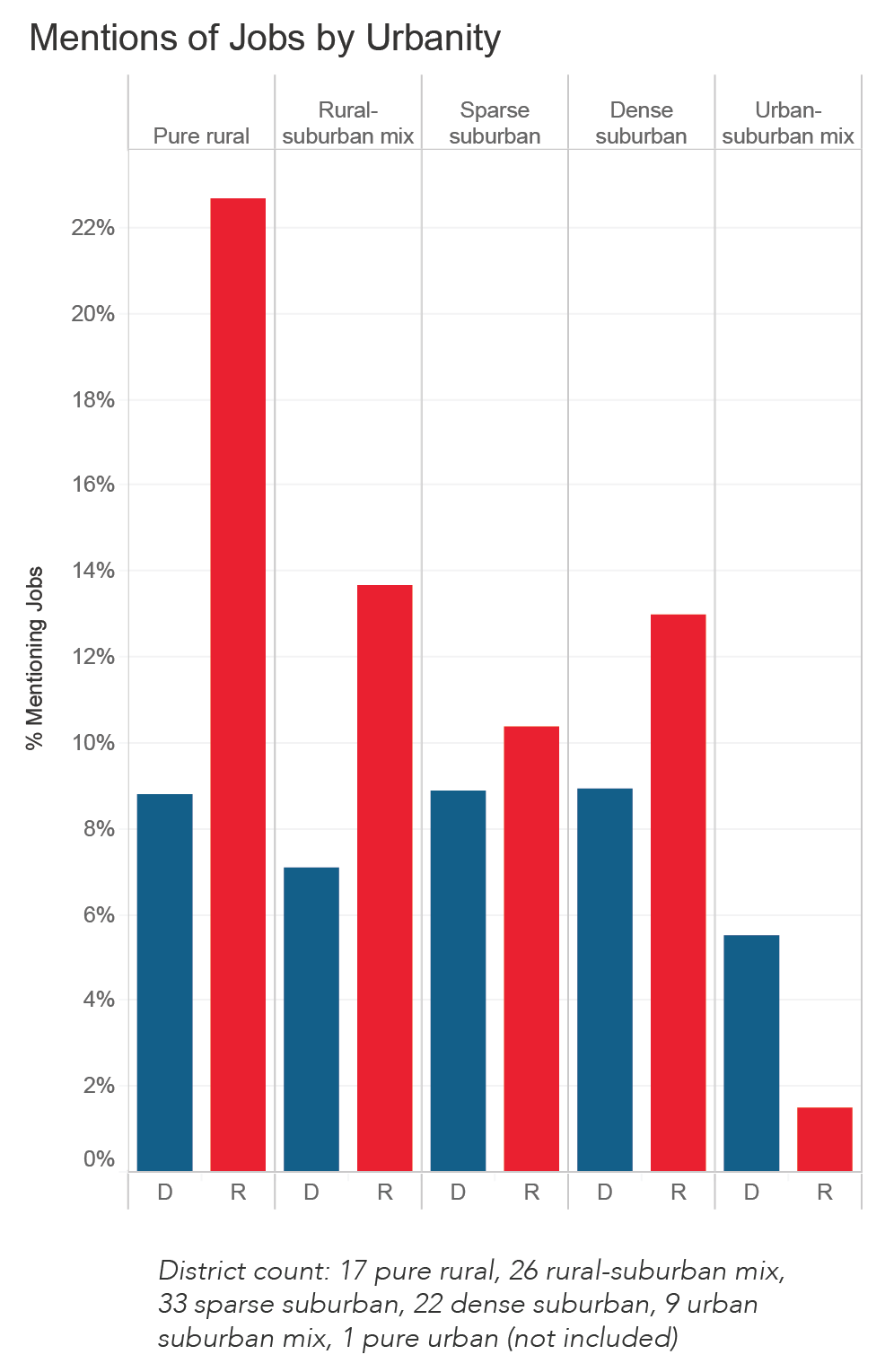

Republicans discussed immigration more than Democrats when comparing districts by a variety of characteristics. One interesting trend emerged when comparing messages surrounding immigration in urban and rural districts. Using CityLab’s six-category density ratings for urbanity, we compared each party’s approach in different types of districts. Note that the plot to the right only shows five of the six categories, as NY-11 is the only district in the dataset classified as “pure urban” and therefore was excluded from this chart. This table contains data from campaign ads on Facebook and television, Facebook posts, Tweets, and website issues pages, which are the primary means of persuasive messaging in the dataset.

One might have expected Republicans to emphasize immigration the most in the rural areas that were key to Trump’s 2016 victory. In fact, Republican candidates were far more likely to discuss immigration in dense suburbs and least likely in the most urban areas in the dataset. Democrats, by contrast, were more likely to discuss immigration in more urban districts. Both parties discussed the issue approximately the same amount in urban-suburban districts.

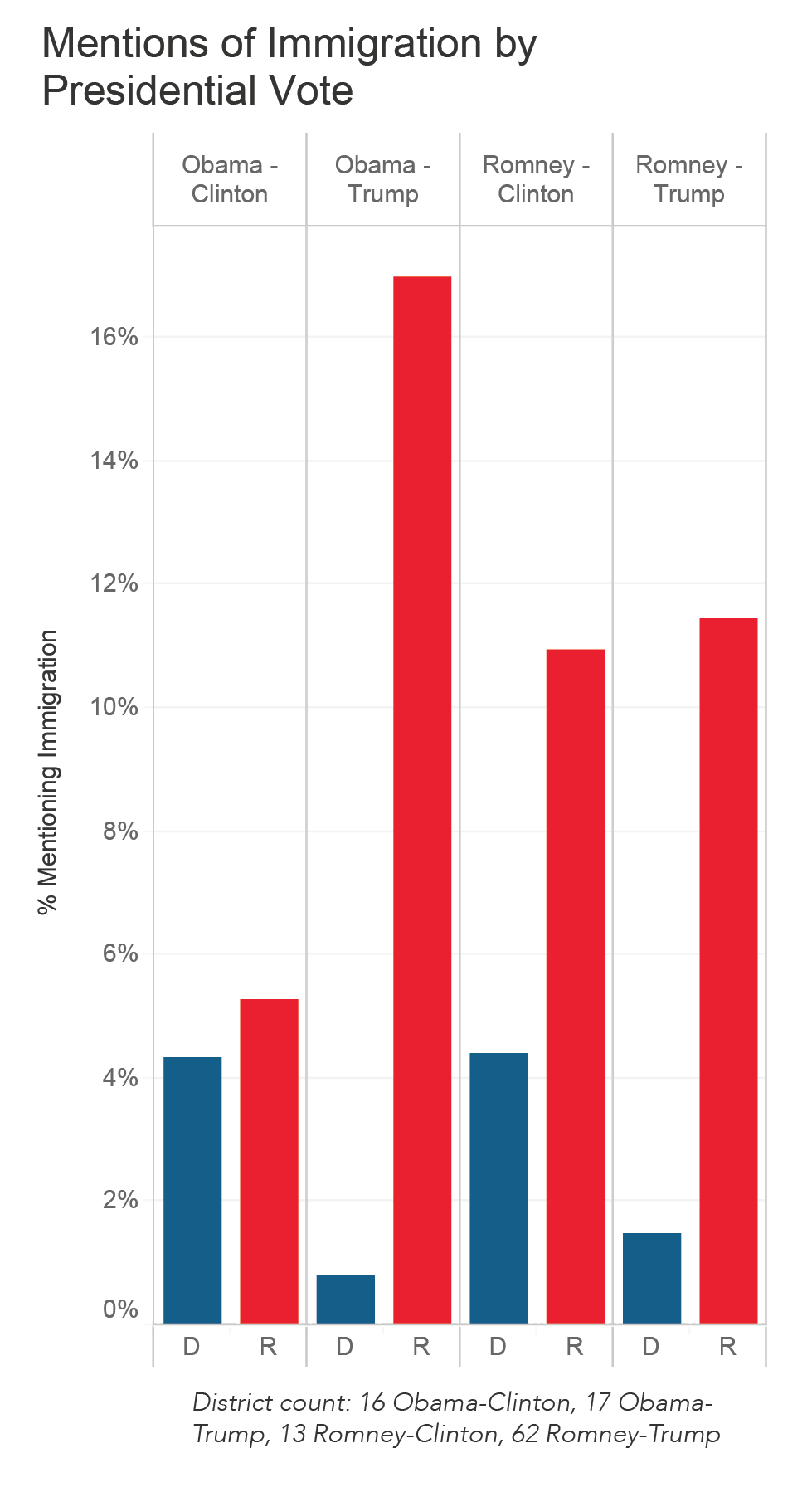

In reviewing past presidential votes and discussion of immigration, we see that Republicans tended to talk about immigration most in Romney-Clinton districts, suggesting a belief that immigration would be an effective wedge issue. Democrats primarily avoided immigration in districts that voted for the Republican candidate in either of the last two presidential contests.

The immigration rhetoric used by Republicans in districts that voted for Trump emphasized securing the border. Communications by Democrats in Clinton districts focused on Trump and his policies tearing families apart. Democratic candidates in Clinton districts were almost twice as likely to mention Trump (25 percent) as their Republican counterparts (13 percent). Looking at the results of these races, it appears this anti-immigrant rhetoric did not help Republicans win. Of the 13 Romney-Clinton districts up for reelection in 2018, 12 Republican House members lost their seats. Only one Congressman from a Romney-Clinton district, Will Hurd (TX-23), will return to the Capitol after the 2018 election after defeating his Democratic challenger Gina Ortiz Jones by only a half-point margin.

Among Republicans, candidates were more likely to talk about immigration in “likely Democratic” or “lean Democratic” districts and in districts with an incumbent Democrat or open Democratic seat, rather than in districts where Republicans were more likely to win. Democrats were more likely to talk about immigration in minority-majority districts, likely expecting their support for this social issue to resonate with voters.

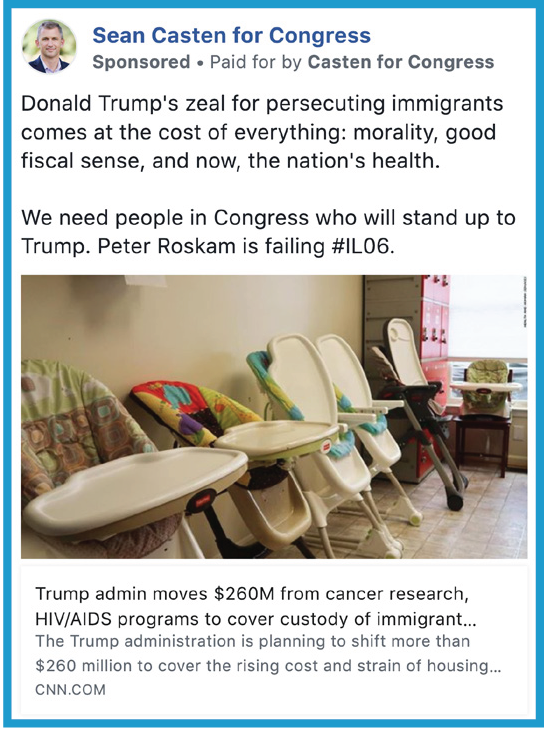

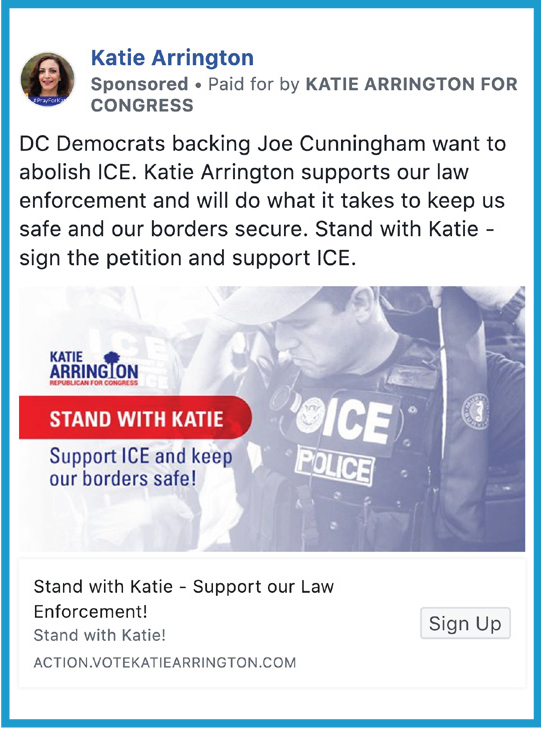

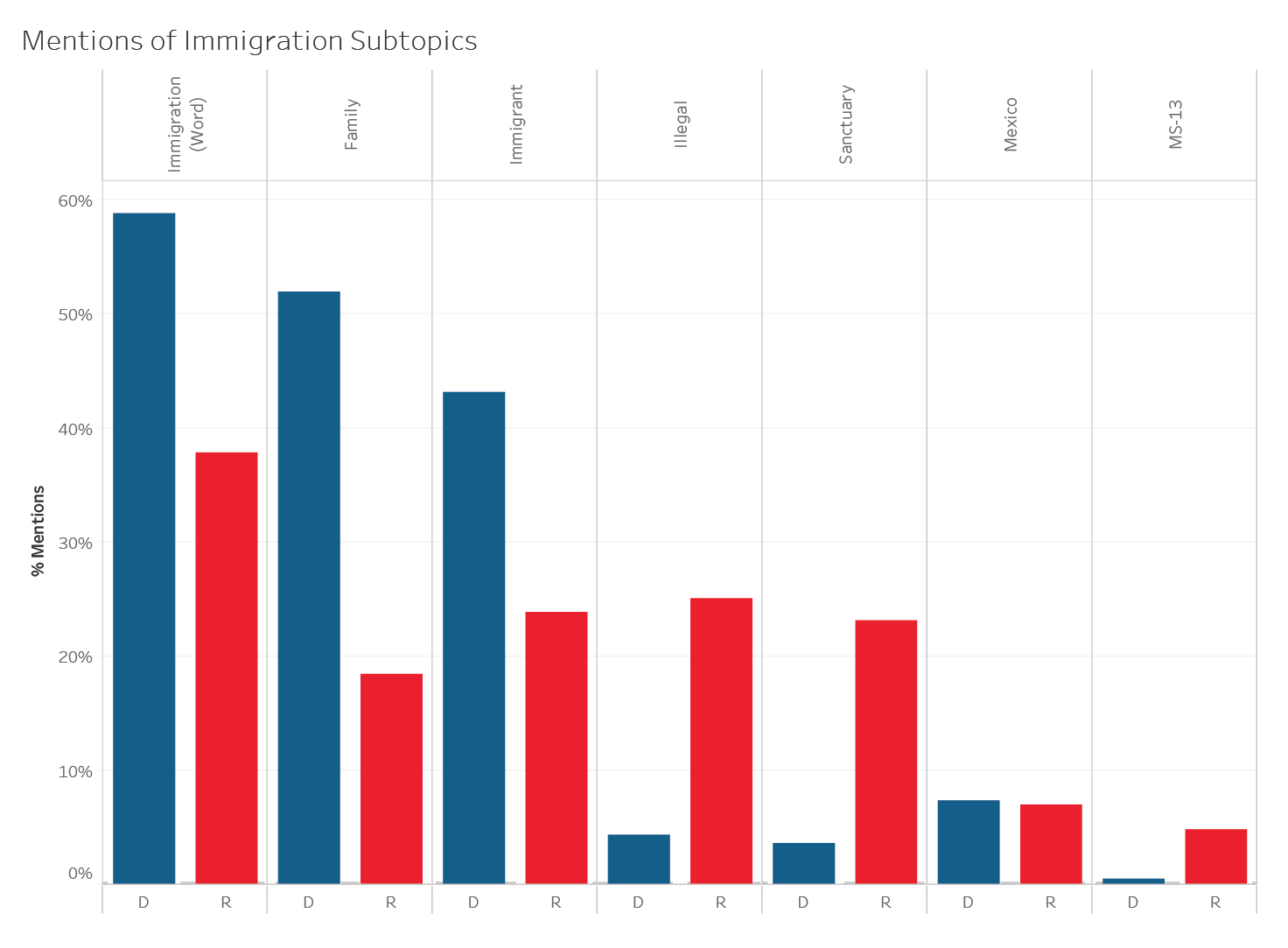

Democratic congressional candidates did not spend much time discussing immigration, but when they did, their focus was on immigrants, families, parent-child separation at the border, and Trump. Democratic references to MS-13 and sanctuary cities were almost non-existent. Republicans, by contrast, frequently used the term “illegal” and were much more likely to reference the idea of sanctuary cities and MS-13.

Looking at each side’s owned words further highlights the stark difference in the parties’ takes on immigration.

| Partisan Political Labels

In this section, we examine how parties use political terms like “Democrat,” “Republican,” “liberal,” and “conservative.” Unless self-identifying as a Democrat or Republican, candidates usually use these terms in a pejorative manner to identify or even demean their opponents.

We also take a closer look at how people talked about Donald Trump and Nancy Pelosi. While both were treated as national figures and were frequently used to signify partisan heuristics, Nancy Pelosi was particularly demonized by the right. Anti-Pelosi attacks associated other Democratic congressional candidates with her in an attempt to diminish these candidates’ favorability and generalize the candidates’ political viewpoints.

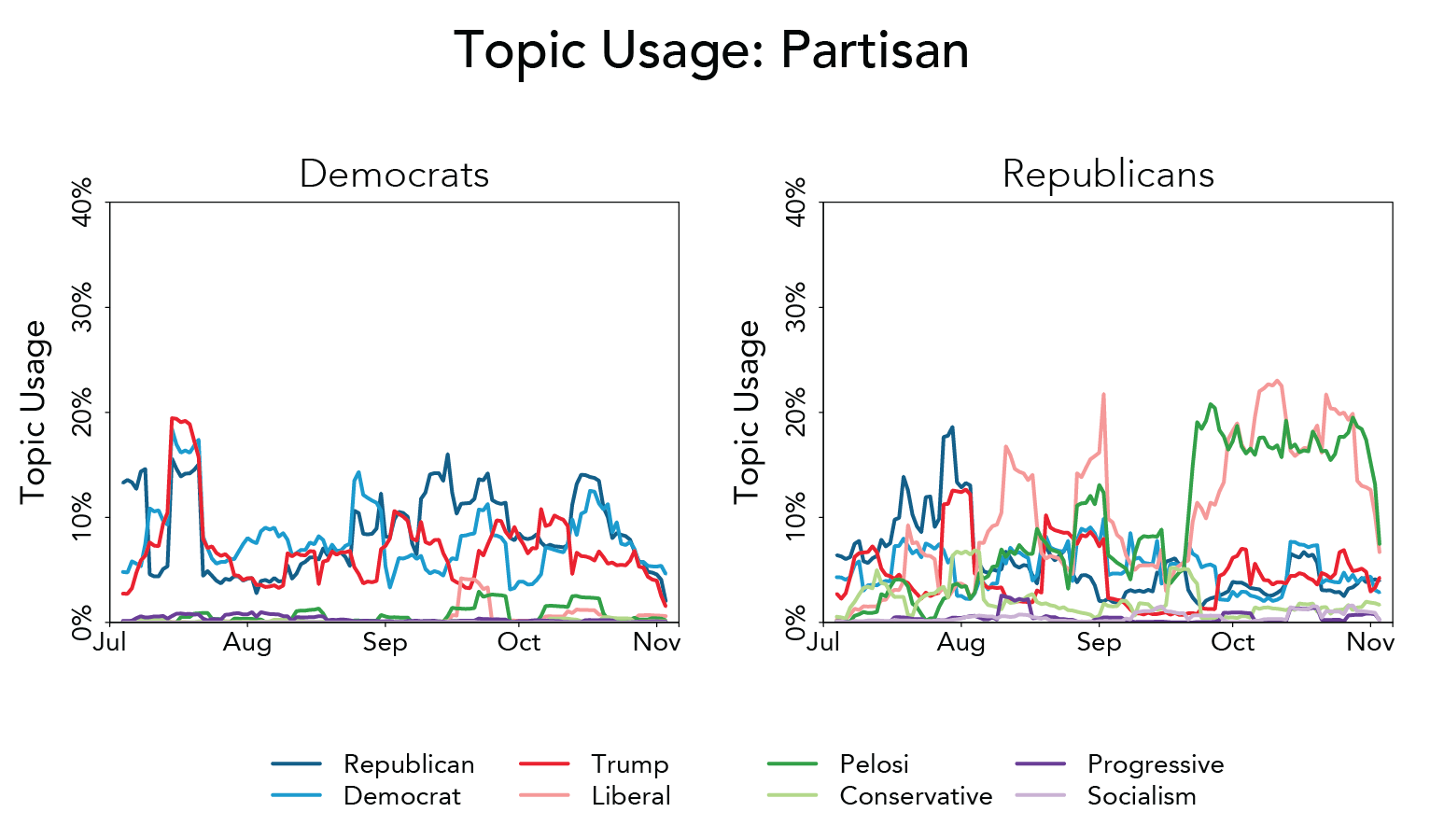

Republicans consistently relied on partisan political terms to attack their opponents and did so more frequently than Democrats. The plot below shows partisan terms used by each party’s communications from July 2018 through the conclusion of the election. Each party used their own party identifier most (e.g., Democrat and Republican) and in a positive way, while other subtopics illustrate themes used by candidates to attack their opposition.

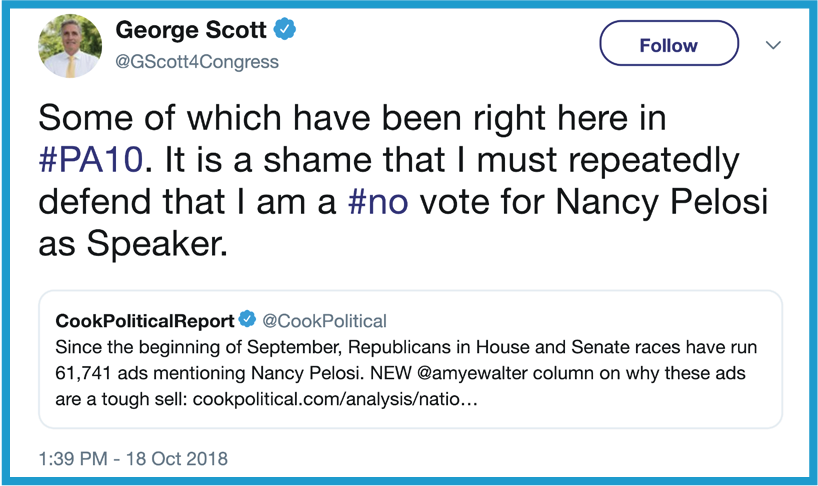

Republican usage of “liberal” and “Pelosi” was similar to their use of other terms until the end of September, at which point both topics became vastly more prominent. Democrats referenced mostly Trump and Republicans but refrained from turning “conservative” into a pejorative in the same way “liberal” had been used against them. Democrats almost never mentioned Nancy Pelosi, and neither party used the term “progressive” much.

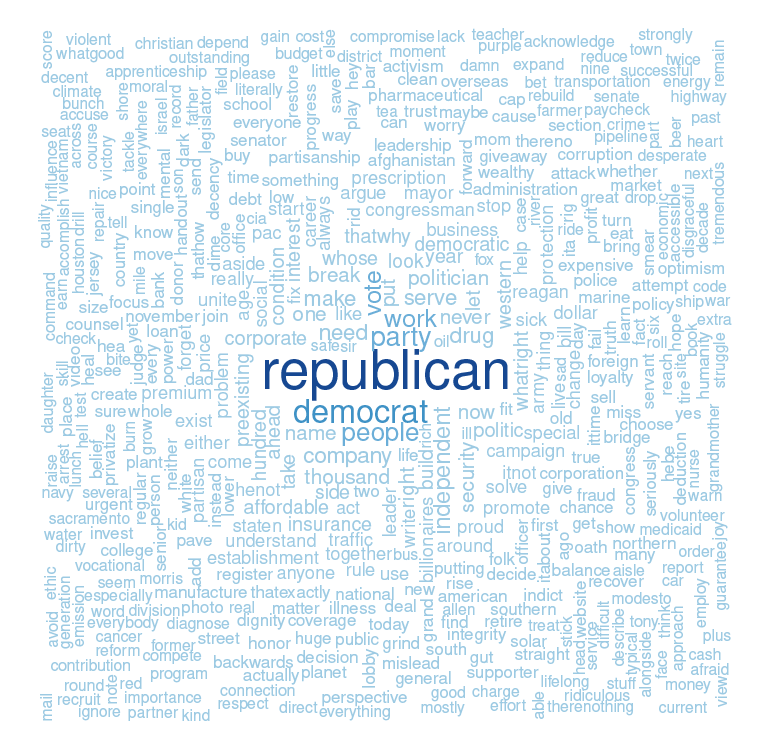

Looking at each party’s owned words gives a sense of how parties use political terms in their arguments.

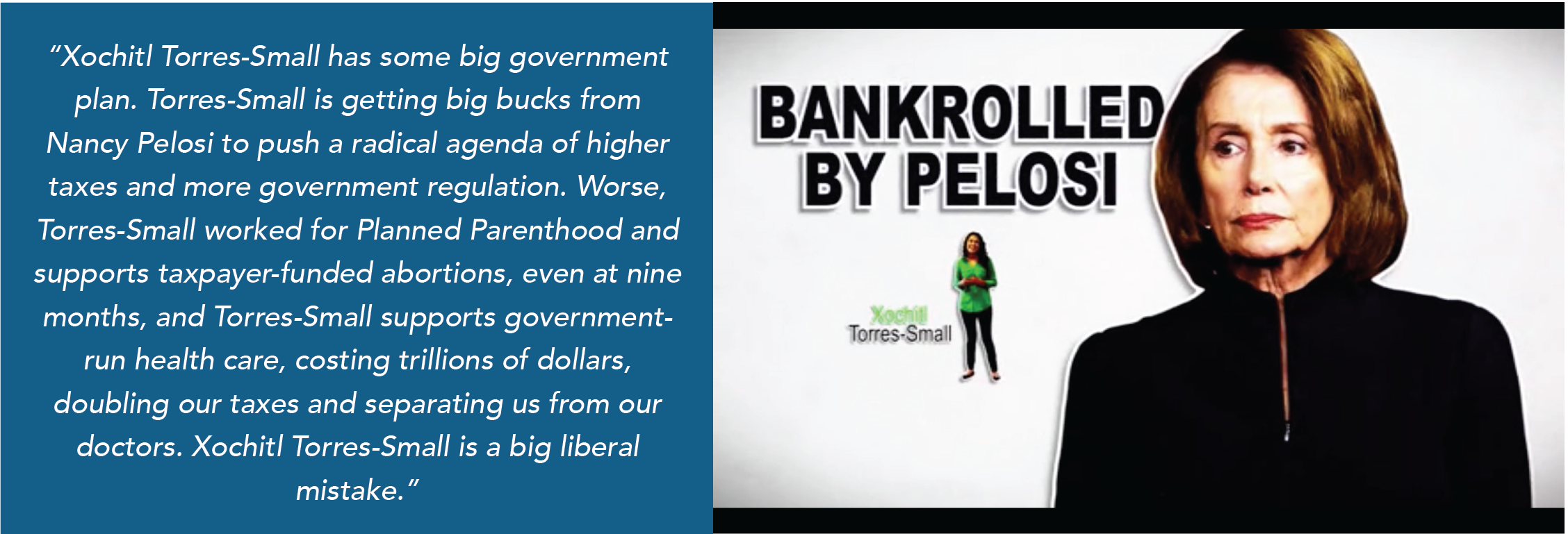

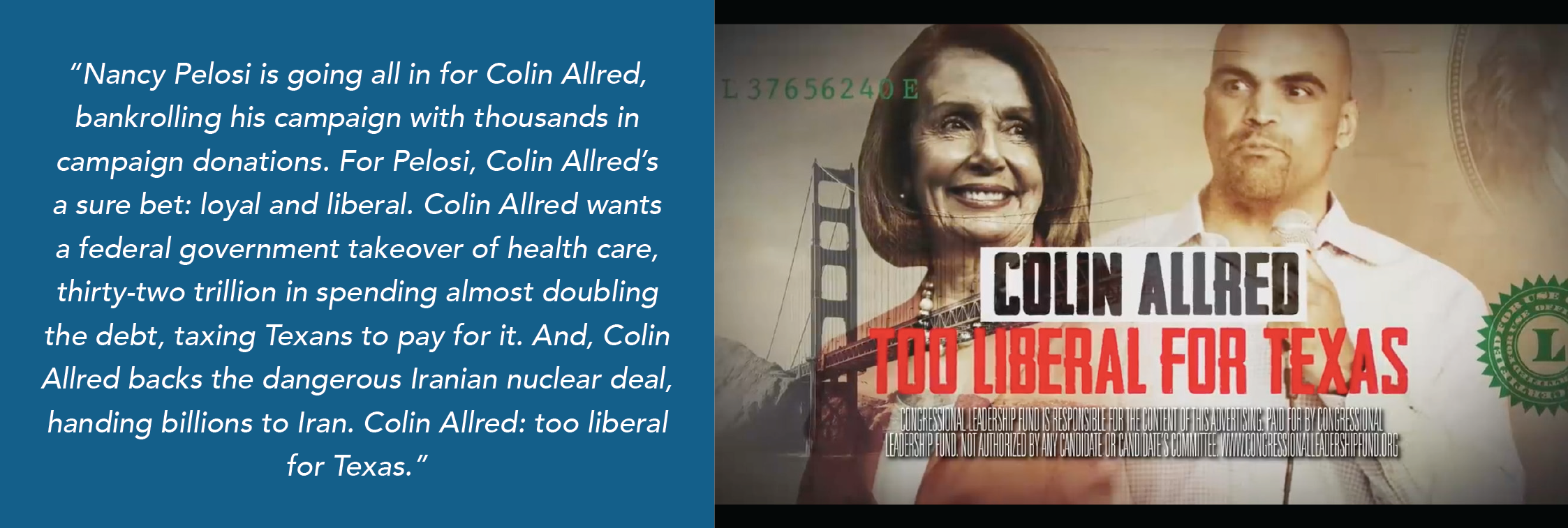

Republicans were more likely than Democrats to use “liberal” and “Pelosi,” most often as epithets intended to tar their opponents with negative connotations. This reductive approach amounts to name-calling, but their extensive use of these terms highlights how Republicans have been effective by using the same messaging year after year: Republicans created and can now deploy a set of symbolic terms that serve as shorthand for a broader range of arguments. These symbolic terms are put to use with more specific claims about what Democrats will do once in power, as exemplified by this campaign-sponsored television ad run by Yvette Herrell, the Republican candidate in NM-02:

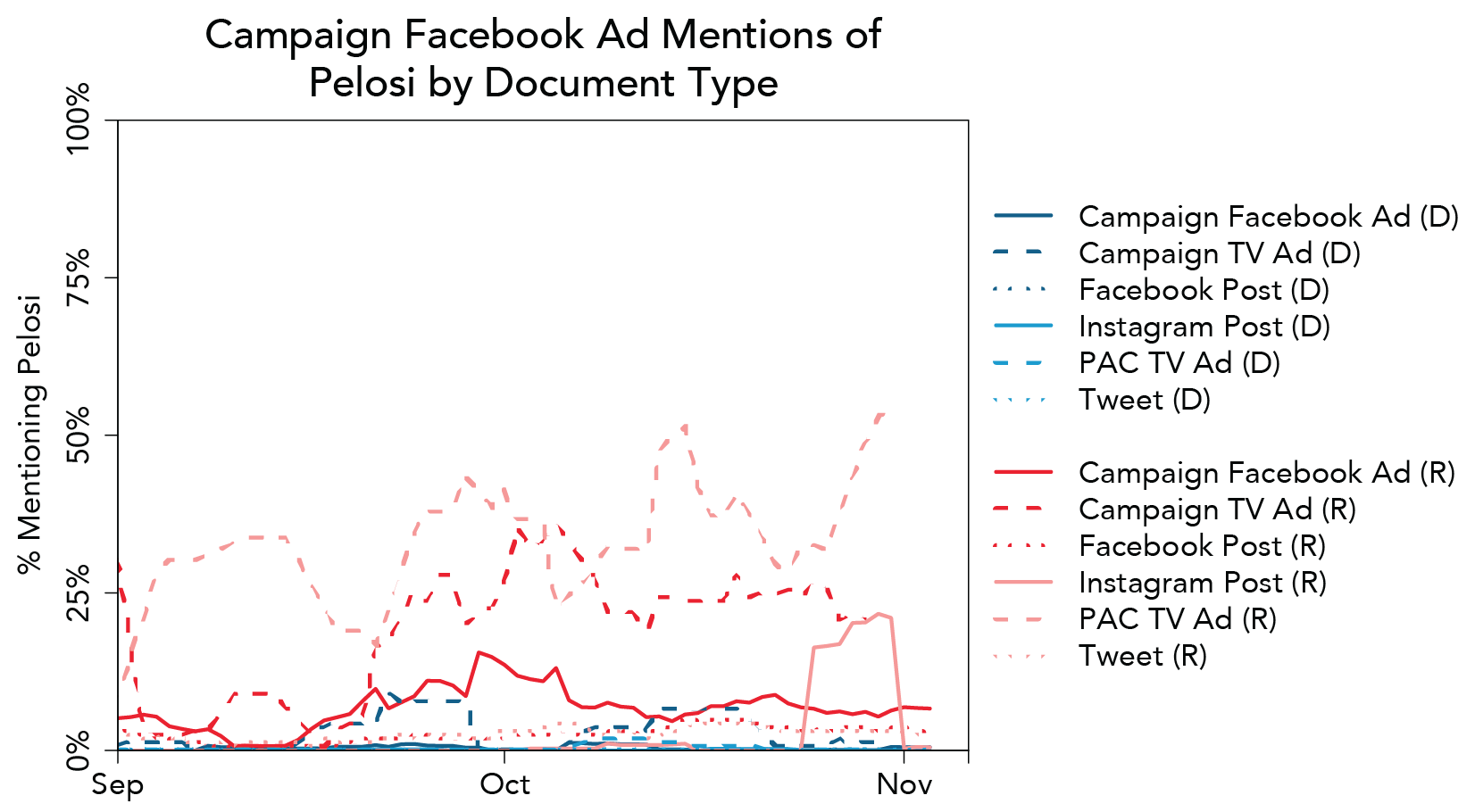

| Nancy Pelosi

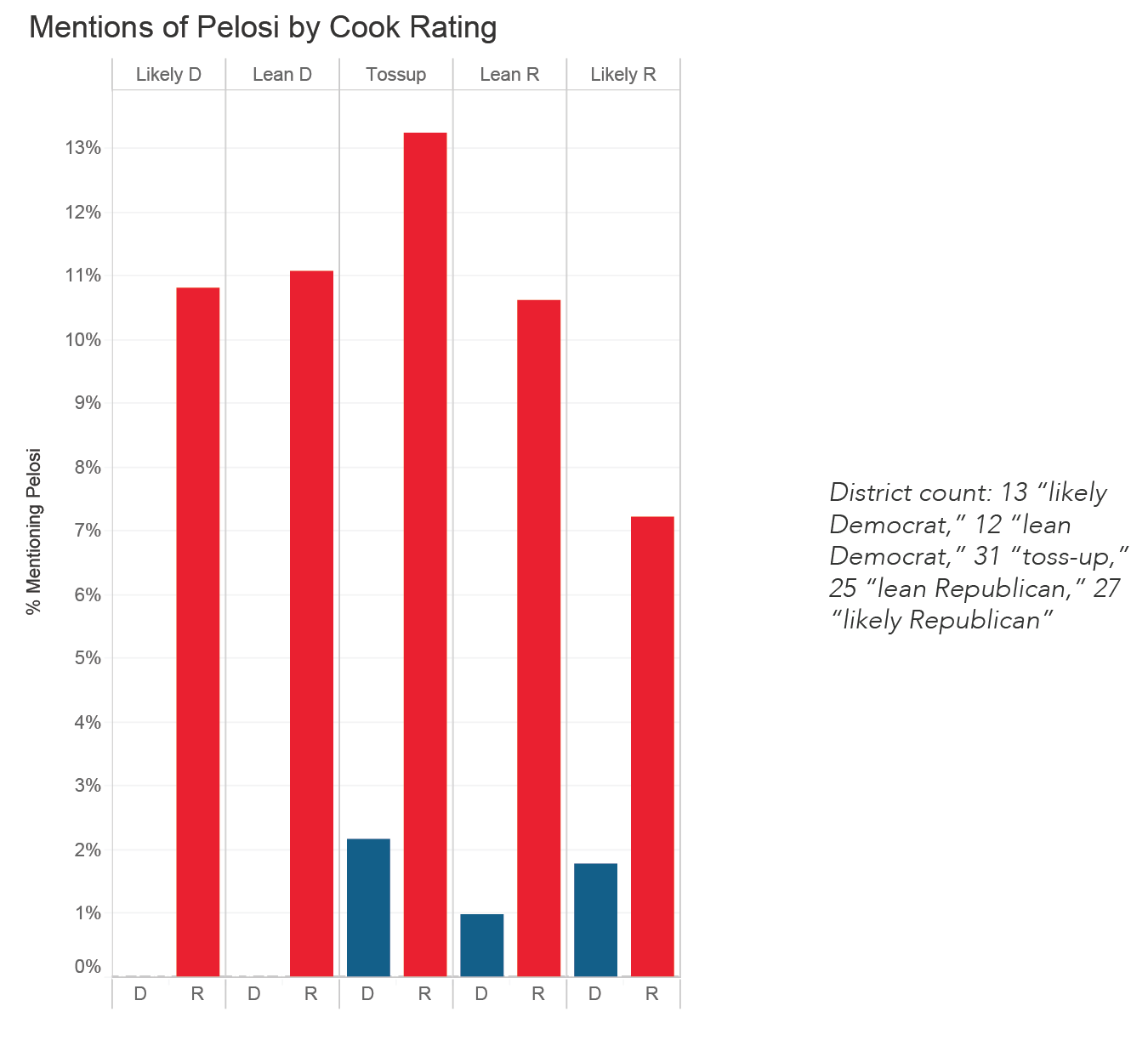

Republicans were intentional in their demonization of Nancy Pelosi. While Democratic mentions of Trump decreased over time, Republicans ramped up their focus on Nancy Pelosi as Election Day approached, attempting to use Pelosi’s possible return as Speaker as a motivator for their base. Republican communications tied other Democratic congressional candidates to Pelosi, portraying them as her loyal, liberal followers, even if they were not incumbents. References to Pelosi were almost exclusively in the form of Republican attacks on Democrats. Television ads by Republican PACs or campaigns comprised a majority of these references, while Facebook ads were a distant third.

The word clouds below show the most frequently used terms by each party while discussing Pelosi. There were far fewer references to Pelosi overall on the Democratic side, and among those few references, Democrats generally talked about new leadership and whether they would support Pelosi for Speaker, while Republicans talked about a “liberal Pelosi agenda” that included higher taxes, using terms like “radical” and “extreme.”

An attack ad sponsored by the Congressional Leadership Fund serves as an example of this attack. The ad portrayed Colin Allred, the Democratic candidate in TX-32, as funded by Pelosi and willing to be her “loyal and liberal” supporter:

In the end, Colin Allred defeated eight-term incumbent Pete Sessions by more than six points.

References to Pelosi were most common in “toss-up” districts, followed by “lean Democratic” districts, as seen in the graph on the next page.

In cases when Democratic communications did reference Nancy Pelosi, they were most frequently by candidates in competitive or Republican-leaning areas, responding to attacks comparing them to Pelosi by saying they would not support Nancy Pelosi for Speaker.

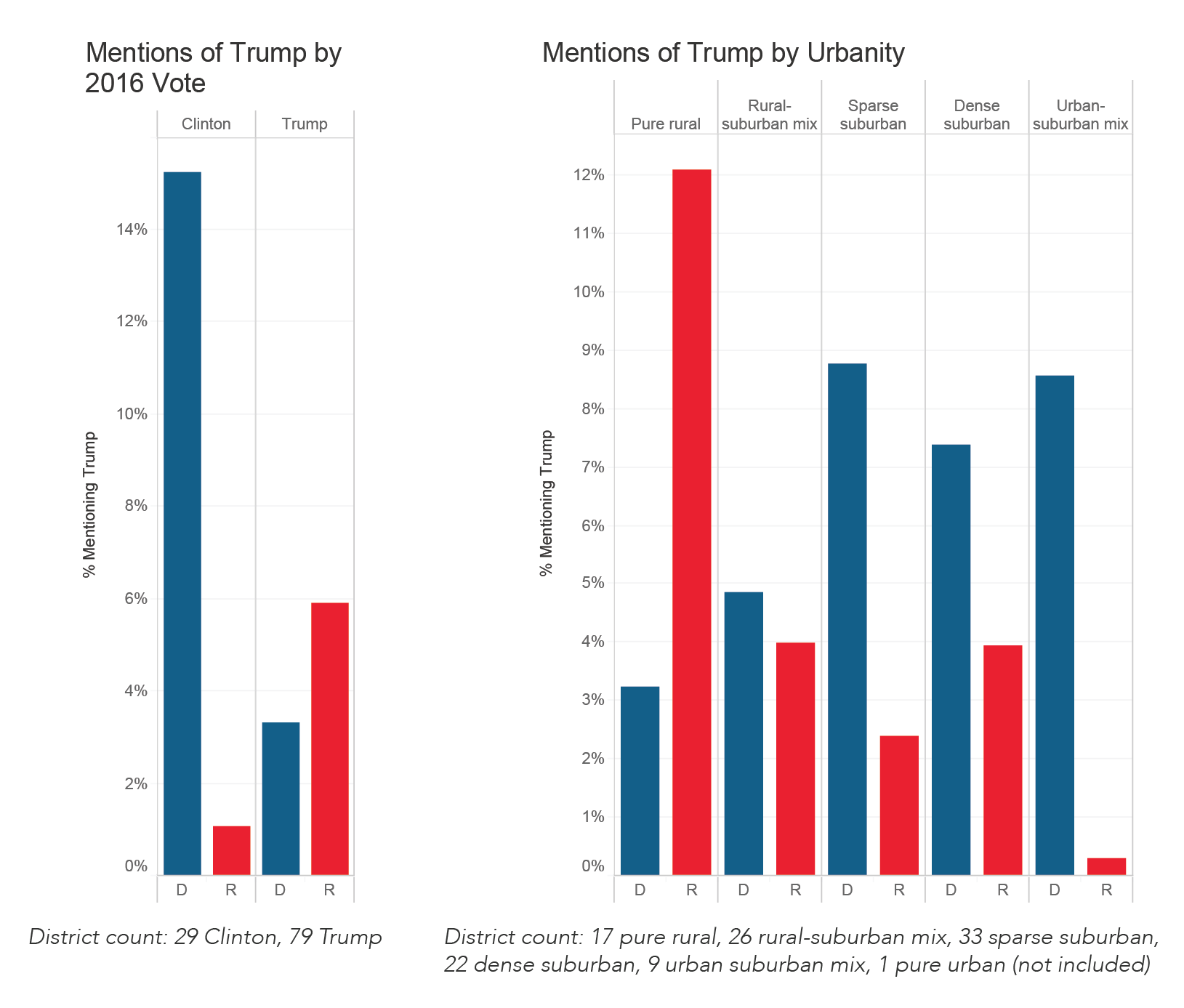

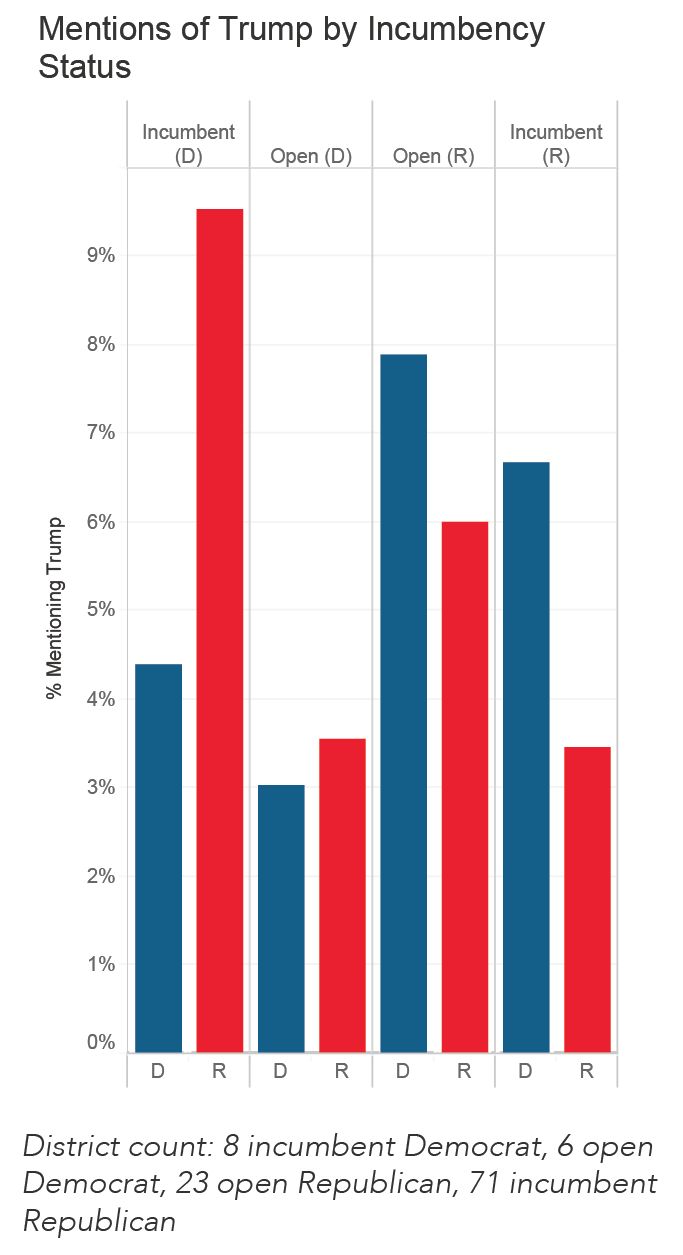

| Donald Trump

Donald Trump was referenced frequently in both Democratic and Republican ads. Trump’s name can be a rallying cry for those who agree with him and a unifying threat for those who oppose him, both factors that can drive participation on Election Day. Unlike Pelosi, he is the president and therefore far more relevant in driving the major political issues today.

Not surprisingly, Republicans discussed Trump more in districts where he won in 2016, as well as in rural districts. Democrats did the opposite, talking about Trump more in districts that voted for Clinton in 2016 and urban districts. Driving the difference was the sentiment around Trump: Republicans connected to pro-Trump voters with a pro-Trump message, while Democrats connected to anti-Trump voters with an anti-Trump message, like supporting immigration reform in light of Trump’s restrictive immigration policies.

One noteworthy finding was that Republicans talked about Trump most in districts currently held by Democrats, and Democrats did the same in districts held by Republicans. This likely reflects the battlefield, as the only Democratic-held seats where Republicans were competing had been won by Trump in 2016, while Democrats were most aggressive in seats left open by Republican incumbents. This trend may also reflect a calculated effort by Republicans to invoke Trump as a means of rallying the base.

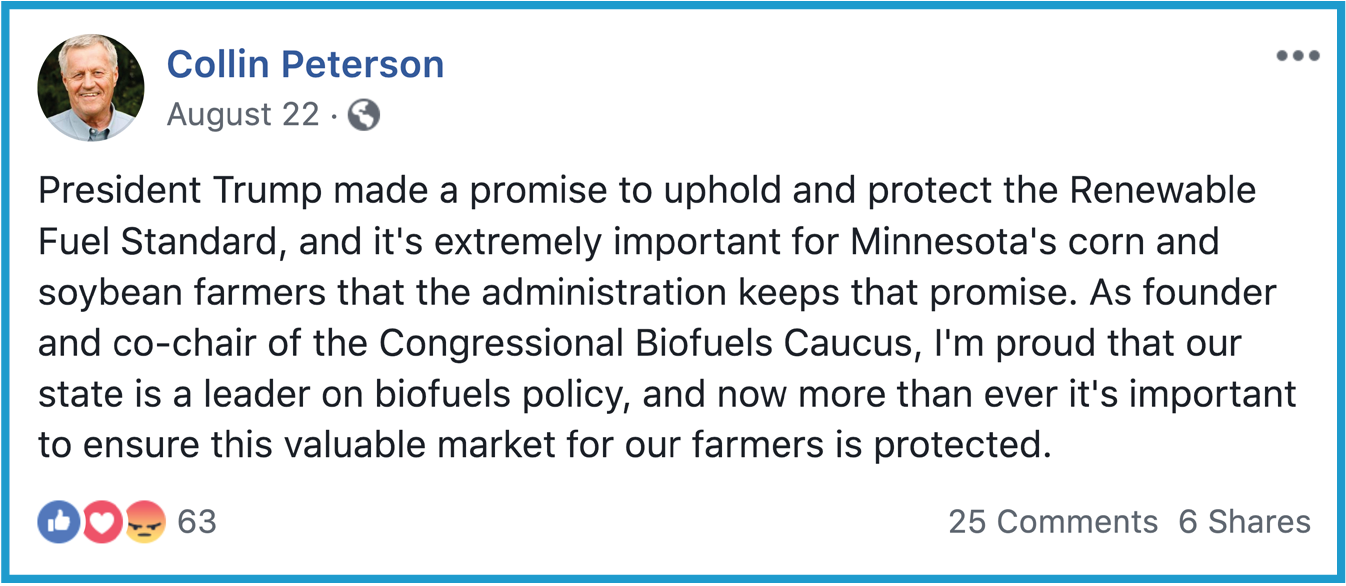

Those Republican-leaning competitive districts with a Democratic incumbent were also the source of rare instances of positive references to Trump by Democrats. For example, Democrat Collin Peterson (MN-07), whose district voted for Trump overwhelmingly (67 percent of the Trump-Clinton two-way vote), positively acknowledged Trump in a Facebook post supporting the Renewable Fuel Standard.

Still, this (mild) pro-Trump sentiment was extremely rare. Democratic references to Trump were overwhelmingly negative, and Democrats in districts that voted for Trump tended to avoid discussing him altogether.

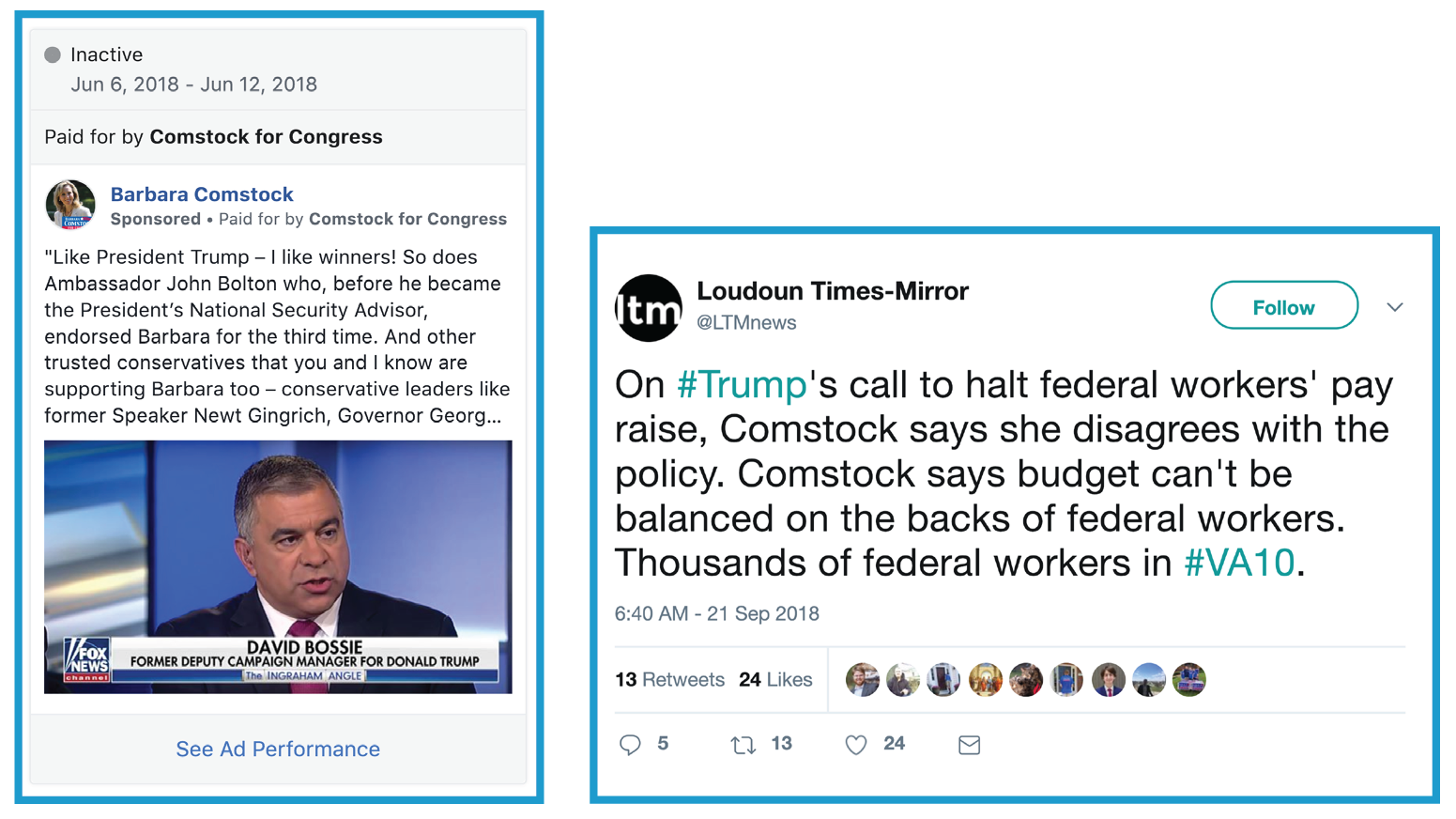

Republicans acted similarly when trying to win in districts that voted for Hillary Clinton in 2016: they were more likely not to mention Trump at all. Reviewing communications from Republican Barbara Comstock (VA-10) and allied PACs as an example, all pro-Trump mentions occurred before the June 12th primary, except for a Facebook post and tweet in late June about a non-polarizing issue (Alzheimer’s & Brain Awareness Month). Ahead of her primary, her campaign shared a few pro-Trump Facebook ads, but after the primary, we found only one communication referencing Trump from her campaign: a retweet from the county newspaper saying she opposed Trump on freezing federal workers’ pay.

By contrast, her opponent, Jennifer Wexton, portrayed her as “Barbara Trumpstock,” doing Trump’s work in Congress. Wexton and allied PACs referenced Trump 69 times between August and Election Day in Facebook Ads, television ads, and social media. Wexton defeated Comstock by more than 12 points.

Among Democrats, white candidates tended to talk about Trump more than candidates of color. Democratic candidates in majority-minority districts were more likely to talk about Trump than in majority-white districts. These Trump references generally tied the Republican opponent to Trump and attacked the candidate for Trump’s policies.

| The Economy

In almost any other political context, the economy would have been a leading topic, especially among incumbent-party candidates eager to capitalize on recent news appearing to show a strong economy. Republicans did not spend much time on economic topics, however, and when they did, they were more likely to deliver warnings about “liberals,” government, and Nancy Pelosi than to claim credit for economic success.

Word clouds below show the most frequently used terms by each party when talking about the economy in campaign-sponsored television ads.

Democratic candidates tended to talk about tax breaks, corporations, special interests, and the need to protect Social Security, while Republicans emphasized jobs, taxes, and the threat of “liberal” Nancy Pelosi and big government.

Considering intra-party differences, we found Democrats talked about the economy roughly twice as much in majority-white districts as they did in majority-minority districts. Otherwise, there were no substantial differences by candidate race, candidate gender, or Cook rating.

Republicans talked about the economy most in districts with an incumbent Democrat and rural districts. They talked about the economy substantially less in Obama-Clinton districts than elsewhere, a surprising finding considering Republicans could have used a strong economy as a motivator to appeal to voters in districts that historically supported Democrats.

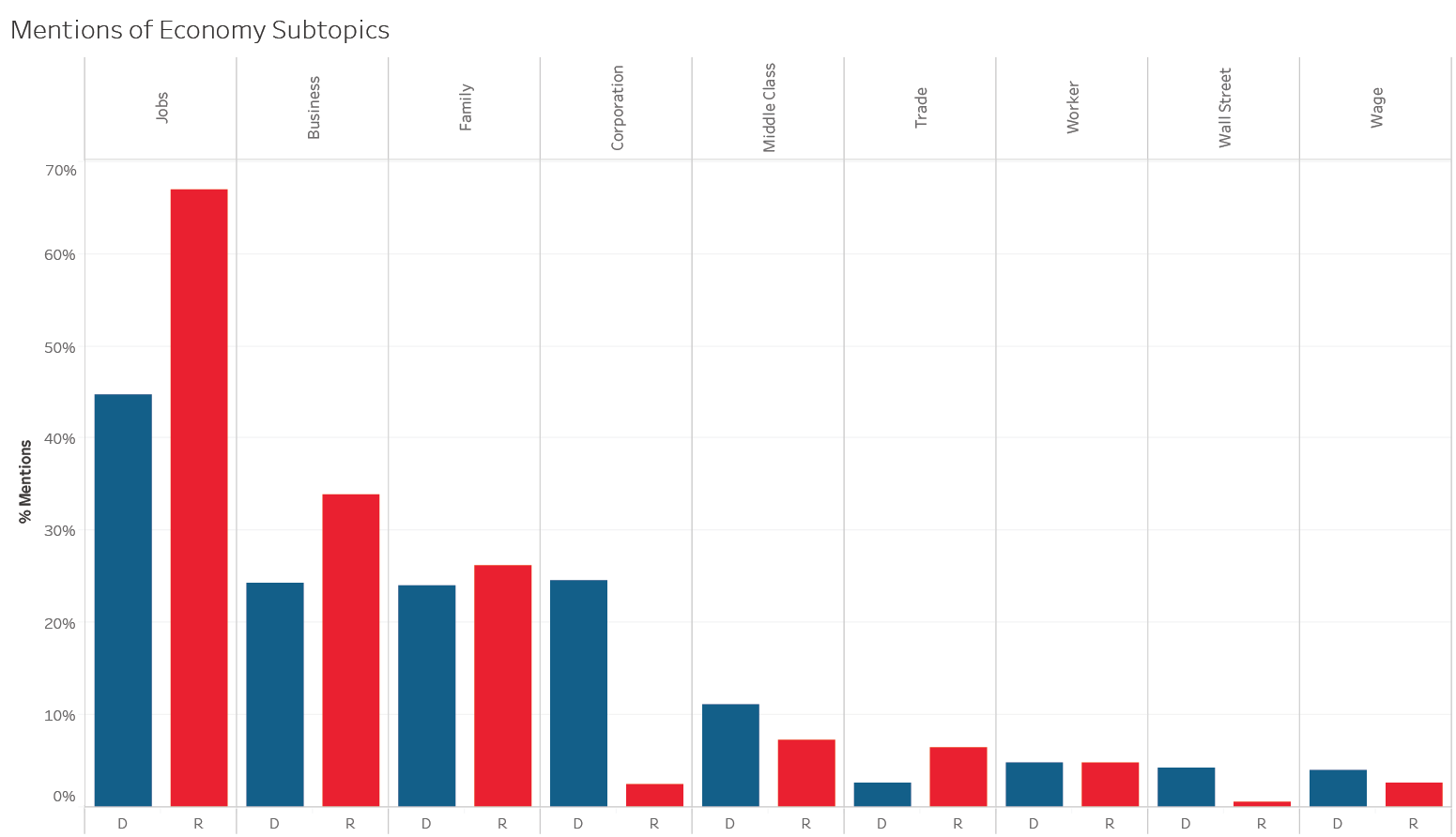

Both parties talked about jobs, but Republicans more so, mentioning “jobs” in 67 percent of their communications on the economy, while Democrats only used the term 45 percent of the time. The other notable difference is that Republicans largely avoided the word “corporation,” while 25 percent of Democratic economic communications mentioned corporations. Democratic communications on jobs were likely to discuss the need to bring quality jobs to their region.

Candidates from both parties were more likely to talk about jobs in districts where they had a higher likelihood of winning: Republicans talked about jobs most in “likely Republican” districts, whereas Democrats talked about jobs most in “likely Democratic” districts. Democrats talked about jobs most in districts with an incumbent Democrat, but Republicans followed an inconsistent pattern in terms of incumbency status, talking about jobs in districts with incumbent Democrats almost as much as they talked about jobs in incumbent Republican districts. Republicans talked about jobs most in rural districts and least in Obama-Clinton districts.

| Business

Republicans were more likely to frame economic arguments in terms of helping business. In campaign television ads, nine percent of Democratic ads referenced business compared to 12 percent of ads from Republicans. Candidates from both parties touted “small business owner” as a credential for office.

When Republicans talked about small businesses, candidates were usually: (1) touting their candidate’s credentials as a small business owner, or (2) arguing Trump tax cuts helped small businesses, either saying they would continue those policies or claiming the Democratic opponent would reverse the tax cut or raise taxes thereby hurting small businesses and families.

Republicans discussed all business more generally in the same way they talked about small business: there was really no differentiation in their philosophy about the two; all business is good business, and tax cuts help businesses and families.

One striking example of Republican message discipline is that Republican candidates almost never used the word “corporation.” As we saw in the previous section, Democrats used the term fairly frequently. However, of more than 51,000 Republican documents in the dataset, in communications ranging from social media to television ads to websites, there were only 167 mentions of either “corporate” or “corporation.” Many of these were social media posts referencing a specific company or organization’s name, highlighting a campaign stop, or a discussion of the supposed benefits of lowering corporate tax rates to create jobs.

Like Republicans, Democrats highlighted “small business owner” as a credential for office, though they also used the term to argue that Republican policies hurt small businesses while helping large corporations. Democrats positioned themselves as pro-small-business owner and pro-family, but not as pro-big business. They distinguished between small businesses and big corporations and between working families and billionaires.

| Other Topics

This report highlights the topics that dominated rhetoric in 2018 congressional campaigns. Several topics are notably absent from our overview, as we found they simply did not receive much attention from campaigns. These topics include Russian collusion and the Mueller investigation, voter suppression, criminal justice reform, the opioid crisis, Brett Kavanaugh and the Supreme Court, and foreign affairs.

This report provides a starting place for understanding the 2018 election, and we encourage others to use this asset to conduct further research for the benefit of the progressive community.

Compared to the lack of attention paid to the Mueller probe, mentions of more conventional concerns about good government were more common. Candidates expressed concern about the influence of lobbyists, special interests, corporate money, and PACs, and commonly attacked their opponents for taking money from these groups. Accepting money from pharmaceutical companies was a particularly common accusation. Not surprisingly, candidates on both sides highlighted instances where their opponents were marred by scandal.

Democrats were more likely to talk about good government issues, referencing the topic in 4.4 percent of Facebook posts (versus 1.3 percent of Republican posts), 14 percent of Facebook ads (compared to 2.4 percent of Republican Facebook ads), and 22 percent of campaign television ads (compared to six percent of Republican television ads). Across select districts, special interests were a major campaign issue for Democrats. For example, in CA-45, Democrats attacked Republican incumbent Mimi Waters for accepting donations from pharmaceutical companies, Wall Street, and fossil fuel industries, and in NY-27, the Democratic candidate hammered Republican candidate Chris Collins who was indicted on insider trading charges. Even accounting for these extreme examples, Democratic candidates were more likely to talk about good government as an issue.

| Conclusion

So, what was this election about: health care? Immigration? Taxes? Donald Trump?

Explicit references to Trump were fewer than one would have expected a year ago—Democrats in Clinton districts ran on an anti-Trump message (just under 15 percent of communications mentioned Trump) and discussed Trump more than any other group of candidates, but his presence in the campaign was more environmental than conversational. Even in districts where Trump won in 2016, Republicans only mentioned the president in about six percent of the documents in the data.

Instead of being the center of attention, Donald Trump’s presidency served as the atmospheric background for the campaign, while candidates from both parties focused instead on the issues they thought would drive them to victory. Broad opposition to Trump may have created the opportunities for the Democratic wave that we witnessed on Election Day 2018, but it was the candidates themselves who seized these opportunities.

In the end, our study shows us that Democratic congressional candidates focused overwhelmingly on health care policy. Exit polls suggest that health care was the top issue for midterm voters by a substantial margin, which would appear to validate the Democratic approach. Democrats also pushed back on Republicans’ tax breaks for corporations and wealthy individuals, although this was clearly secondary to health care.

Although explicit references to Trump were less frequent than one might expect among Republicans, it is hard to deny the Trumpian effect on their rhetoric: fear, anger, us vs. them politics, and an overtly racist anti-immigrant stance. Their overall message was fear-based, even on pocketbook issues like taxes and health care: vote for Democrats and your taxes will go up; Democrats’ “big government takeover of health care” will bankrupt Social Security and Medicare.

Many observers assumed that Democrats would be fighting an uphill battle on taxes, trying to explain with some nuance that the “tax cuts” mainly benefit the wealthy, and will blow a hole in the deficit and throw important social programs like Social Security and Medicare into jeopardy. Republicans had a simpler argument: we pass tax cuts, and tax cuts are good for American families and business. In the end, the evidence suggests that the Democrats had a strong message describing the negative impacts of Republican tax cuts.

Following Trump’s lead, Republicans increasingly referenced immigration as Election Day approached. Meanwhile, Democrats in competitive districts largely stayed away from the issue, focusing instead on health care. The topic received the most attention in more progressive areas, districts that are largely suburban-urban and voted for Obama in ’12 and Clinton in ’16.

One clear takeaway is that, at least with an unpopular president in office, the Republican strategy of stoking fear and nationalizing the race (by invoking Nancy Pelosi) did not help them prevent a large Democratic win, the greatest Democratic pickup in the House since Watergate. While perhaps not as unified as Republicans in their talking points, Democrats focused on how to address issues that affect ordinary Americans. They were not baited into letting their opponents dictate the terms of the conversation. The coherent, issue-focused messaging displayed by Democrats in the 2018 midterms appears to provide a blueprint for a successful counter to Republican fear tactics and can perhaps help Democrats continue their success in 2020 and beyond.

| Appendix

The data used for this analysis is available upon request and may be made available at our discretion and in accordance with the terms and conditions of the source of the data. Please contact data_requests@themessinagroup.com to request access.

| Methodology

To better understand the issues and messages driving congressional campaigns in the 2018 election, we collected and analyzed communications from candidates, party committees, and political action committees (PACs) in competitive districts (anything rated as “likely,” “lean,” or “toss-up” according to the Cook Political Report as of October 8, 2018). These communications were comprised of a variety of sources, including television ads, social media posts (from Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook) by candidates/campaigns, party committee websites, campaign websites’ issues pages, and campaign Facebook ads.

The method used to collect the data in this report varied by data type. Candidate website text was obtained by going to each website, clicking on the link to the “issues” section (some candidates used other names, such as “agenda” or “policy”) and copying and pasting all text into a plain text document. For Facebook posts, we went to each candidate’s Facebook page, scrolled down to the beginning of June 2018, and copied all content into a plain text document. For Facebook ads, we used the Facebook Ad Archive—searching for each candidate and identifying the name of their campaign committee. We then searched for all ads from the committee and copied and pasted them into a plain text document.

Party committee sites were scraped using code we developed for the project—our script obtained the complete list of districts in which either party had created a page and then went to the page and retrieved the content. Television ads were obtained through an arrangement with Amplify, a media buying company. Amplify provided information about each buy, as well as a copy of the video. We then used the web-based transcription service Trint to generate transcripts of each ad. These transcripts were then manually reviewed by our staff to ensure accuracy. We obtained Instagram posts using the publicly available software 4K Stogram. Tweets were obtained through our subscription to the Twitter API, using a Python script to retrieve tweets.

Only text content was analyzed in this report, and only English language content was analyzed. The dataset includes a variety of media but is not comprehensive of all communications from campaigns.

| Caveats About The Data

There are a few caveats about the data that should be addressed. First, there was a significant amount of manual work involved in collecting this data. As with any dataset, there may be some gaps or errors, although we have taken every precaution to be as thorough as possible in identifying and fixing such errors. Processes could not be easily standardized across platforms or races, and the sheer volume of information made it nearly impossible to check every entry manually.

Additionally, not all campaigns communicated in the same way. For example, not all candidate websites contained an issues section. Of the 108 districts in the dataset, all Democratic candidates had an issues section on their website, but 10 Republicans did not.

Aside from tables showing raw counts of content types, all charts and figures in this report are weighted so that each district is treated equivalently. This was done to ensure that a single district that produces a large amount of content does not overwhelm the analysis. Television ads are also weighted according to the size of the spend so that we treat more expensive ad buys as a larger emphasis on the message of the ad.

The table to the right indicates the number of documents of each type by party. This appendix also contains a breakdown of documents by district.

This analysis primarily focuses on a handful of issues that were central to the midterm elections, which has been validated by election night exit polling and subsequent post-election surveys such as the November 2018 Navigator report. Those issues include healthcare, Social Security and Medicare, taxes, immigration, Donald Trump, Nancy Pelosi and partisan political terms, and the economy.

Keyword searches were used to identify topics. A dictionary is provided on the following page to show which terms were used to search for each topic. Districts were also classified in terms of urbanicity, whether the district voted for Trump or Clinton in 2016, incumbency status, and Cook Political Report classification, and we recorded candidate demographics including race and gender. We considered each of these characteristics in conjunction with information about individual districts to identify larger themes and trends.

| Keyword Search Terms

- Health care: “health care”, “healthcare”, “affordable care act”, “ACA”, “Obamacare”, “pre-existing condition”, “age tax”, “Medicare”, “Medicaid”

- Immigration: words or phrases containing the string “immigr” (i.e., “immigration”, “immigrants”), the string “Mexic”, “border”, “caravan”, “MS-13”, “MS13”, “illegals”, “sanctuary”, “abolish ICE”

- Economy: “job”, “wage”, “Wall St”, “trade”, tariff, “worker”, phrases containing the phrase “working famil” (i.e. “working family” or “working families”), “middle class”, “corporation”, “business”, “economy”

- Political: “liberal”, “conservative”, “progressive”, “democrat”, “republican”

- Tax bill: “tax” in conjunction with any of the following words: “reform”, “cut”, “bill”, “increase”, “plan”, “scam”, “relief”, “law “raise”, “break”

- Tariffs: “tariff”

- Trump: “Trump”

- Pelosi: “Pelosi”

- Health care word: “health care”, “healthcare”

- Medicare: “Medicare”

- Medicaid: “Medicaid”

- Economy word: “economy”

- ACA/Obamacare: “ACA”, “Affordable Care Act,” “Obamacare”

- Pre-existing conditions: the phrase “existing condition” (i.e., variants of “pre-existing condition”)

- Age tax: “age tax”

- Jobs: “job”

- Wage: “wage”

- Wall St: phrase containing the string “wall st” (i.e., “Wall St.” or “Wall Street”)

- Trade: “trade”

- Worker: “worker”

- Working families: phrase containing the string “working famil”

- Middle class: “middle class”

- Corporation: “corporation”

- Business: “business”

- Small business: “small business”

- Conservative: “conservative”

- Tax/Taxes: “tax”

- Tax cut: “tax cut”

- Tax bill: “tax bill”

- Tax reform: “tax reform”

- Veteran: “veteran”

- Immigrant: “immigrant”

- Immigration word: “immigration”

- Mexico/mexicans: words or phrases containing the string “Mexic” (i.e. “Mexico” or “Mexicans”)

- Border: “border”

- Caravan: “caravan”

- MS13: “MS-13”, “MS13”

- Illegals: “illegals”

- Sanctuary: “sanctuary”

- Tax increase: “tax” and “increase”

- Tax plan: “tax” and “plan”

- Tax scam: “tax” and “scam”

- Tax GOP: “tax” and “GOP”

- Tax republican: “tax” and “Republican”

- Tax relief: “tax” and “relief”

- Tax law: “tax” and “law”

- Tax raise: “tax” and “raise”

- Tax break: “tax” and “break”

| Count of Document Types By District