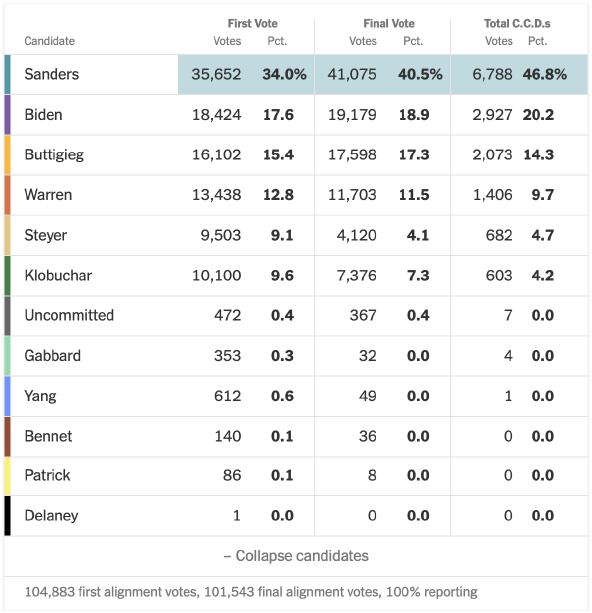

On Saturday evening, the Associated Press called the Nevada caucuses for Senator Bernie Sanders with about 60% of precincts reporting. With all of Nevada’s 2,097 precincts reporting, The New York Times shows the following breakdown:

Sanders had an unquestionably strong performance in Nevada, but to understand how things didn’t go wrong on Saturday and why some candidates did well where others fell short, we need to first take a look at how the Nevada caucuses actually work.

In an effort to be more transparent, the Nevada Democratic Party committed to release three sets of results: the first vote, the final vote, and the number of county convention delegates (C.C.D.s) won by each candidate. By reporting the totals from each stage of the caucusing process, outside observers are empowered to check the numbers themselves and, as a result, hold the state party accountable when the votes don’t add up.1

Just like in the Iowa caucuses, candidates must meet a 15 percent viability threshold in the first vote in order to be counted in the final vote total. The first vote is analogous to a popular vote measure in the process and serves as the best metric to compare to pre-contest polls. Next, non-viable groups can (a) join with a viable group, (b) combine with other non-viable groups to achieve viability, or (c) go home. Once this final alignment phase concludes, the vote totals of all viable groups are converted into county convention delegates.2

In addition to reporting three sets of results, the Nevada Democratic Party also introduced early voting to the caucuses. Early voting in Nevada took place between February 15-18, requiring participants to cast a paper ballot that ranks their top three to five candidates in order of preference. Volunteers at the caucus sites are given the data from these early votes and are supposed to act like the early voters are physically present. So if an early voter’s first choice is not viable, they will be realigned to their next ranked choice who has a viable group. Early vote ballots are effectively incorporated into each step of the process and are accounted for in the eventual C.C.D. conversion.

1. The Buttigieg campaign has filed complaints with the Nevada Democratic Party on inconsistencies in how early vote totals were incorporated into the process on Caucus Day.

2. There is a bit of math involved in calculating C.C.D. totals. Each precinct has a set number of county delegates to allocate among viable candidates. In a precinct with 6 county delegates, where two candidates are viable with 46% of the vote after final alignment, the viable candidates would get 3 county delegates each to attend the upcoming convention. Since county delegates are actual people, these numbers are rounded up or down to the nearest integer, which can result in ties. In Nevada, a simple card game is used to resolve the tie. Whoever draws the high card wins the county delegate in question. These C.C.D.s are then converted into pledged delegates, of which Nevada has 36 to award.

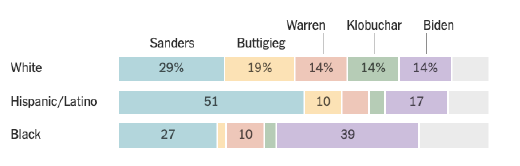

Sanders won handily by all three measures, securing 34.0% in the first vote, 40.5% in the final vote, 46.8% of C.C.D.s won and 24 pledged delegates. Looking back at where Sanders stood in pre-caucus polls (32.5% per RealClearPolitics), the results from Saturday run in line with expectations and show that, while polling Nevada is difficult for a variety of logistical reasons, the polls did a pretty good job of in the run-up to the caucuses. Exit polls show that Sanders won by big margins in Washoe County (Reno) and Clark County (Las Vegas), making a dominant showing in Nevada’s most populous areas. Sanders won 51% of Latino voters and a majority of voters under the age of 45. Despite being effectively anti-endorsed by the leadership of the Nevada Culinary Workers Union, Sanders’ victories at the Bellagio and Mandalay Casino caucuses suggest that Culinary union members actually broke for Bernie, powering him to a decisive win.

The FiveThirtyEight model now rates Sanders’ chances of winning a majority of pledged delegates at 47%, around a 1 in 2 chance of outright winning the nomination. That same model has Sanders running neck-in-neck with Joe Biden for the chance to win the most delegates in South Carolina, giving Bernie a 43% chance to win and Biden a 48% chance. While Sanders leaves Nevada with considerable momentum, it’s important to note Biden remains competitive in South Carolina and was the most popular candidate among Black voters in Nevada; Biden won 39% of voters in this group.

After fourth and fifth place finishes in Iowa and New Hampshire, Joe Biden came in second with 20.2% of county delegates in Nevada. Exit polls show Biden’s support growing throughout the process, from 17.6 percent in the first vote to 18.9 percent after realignment, which translated to 20.2 percent of C.C.D.s and 7 pledged delegates. Biden benefited from the realignment process, possibly capturing support from Steyer and Klobuchar in precincts where they failed to meet the viability threshold. Steyer’s numbers fell from 9.1 in the first vote to 4.1 in the final vote, mirroring Klobuchar’s support bleeding from 9.6 percent to 7.3 percent overall.

Pete Buttigieg also made gains in the realignment phase, moving from 15.4% in the first vote, to 17.3% after realignment, 14.3% of C.C.D.s and 2 pledged delegates. These numbers run slightly behind Buttigieg’s pre-Nevada polls (16.0%). But the polls leading up to the caucuses did a good job of predicting ballpark numbers on how candidates would do.

The incorporation of early vote in the caucuses seems to have had a significant effect on both how voters turned out in Nevada. Preliminary counts indicate that 75,000 participants cast ballots during the early voting period. With all precincts reporting, turnout for the first alignment added up to 104,883 votes, which surpassed 2016 (84,000) but didn’t beat 2008’s record high turnout (118,000). This means that close to three- quarters of all participants voted before the pre-Nevada presidential debate, between February 15-18. This heavy activity during the early vote period likely had a sizable effect on how the final results shook out.

Along those lines, it’s possible that lopsided turnout during early voting made it harder for Elizabeth Warren to capitalize on her highly-praised debate performance because the impact of late-deciders was limited. After the debate, Warren did see a bit of a bump in the polls and her campaign had its best day of fundraising. Warren actually ran behind her polls by about a point (14.0% per RCP), winning 12.9% of the first vote, 11.6% after final alignment, 9.8% of total C.C.D.s and no pledged delegates.

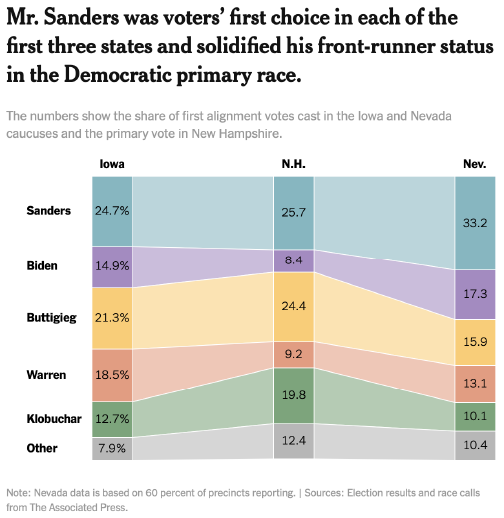

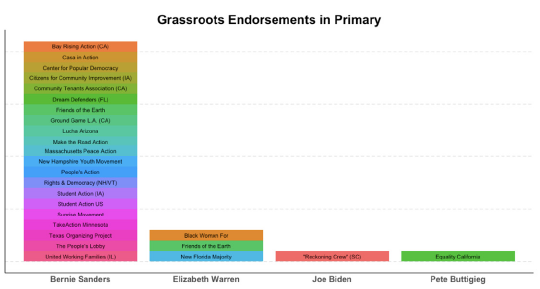

Coming out of Nevada, Bernie Sanders appears to be the clear frontrunner in the 2020 Democratic nomination contest. It’s important to keep in mind that while Sanders is not a prohibitive leader in the field, the high chance that no one wins a majority of pledged delegates (41% per FiveThirtyEight) does not necessarily mean we’re headed to a brokered convention. Although Sanders lacks traditional establishment endorsements (from elected officials and party figures), he leads the race for endorsements among grassroots organizations, per analysis from Data For Progress. In fact, if Sanders wins a plurality of pledged delegates (7 in 10 odds according to FiveThirtyEight), then he might become the nominee anyway. It’s increasingly likely that no one will win a majority of delegates, so we will have to wait and see how the party decides.